Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 4484 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

We are proud to announce that our own contributor and associate Dr. Elizabeth Murray, Ph.D., has been awarded the Anthropology Section's 2018 "T. Dale Stewart Award" at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) 71st Annual Scientific Meeting in late February.

Dr. Murray's involvement with AAFS has included chairing the Academy-wide annual meeting as well as committee-level service in long-term planning, Board of Trustees, and the Student Academy.

Well-known and respected as a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Murray teaches at the University of Mount St. Joseph courses in anatomy and physiology, gross anatomy, and forensic science for the Department of Biology. Her most recent book, published in 2019, is "The Dozier School for Boys: Forensics, Survivors, and a Painful Past."

Our congratulations to her for yet another incredible achievement in her illustrious career. We are glad to count her as a friend and as a contributor to "Medical Terminology Daily" and Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc.

- Details

- Written by: Prof. Claudio R. Molina, MSc

Holly leaf sign.

Click on the image for a larger depiction

The Holly is a tree/shrub of the genus Ilex , with perhaps the most well know being Ilex aquifolium. The plant has shiny prickly evergreen leaves and bright red berries. Cut branches of Holly are widely used as a traditionally Christmas decoration especially in wreaths and Christmas cards as illustrations. “The Holly and the Ivy” is a popular traditional English Christmas carol.

The [Holly leaf sign] refers to the appearance of calcified pleural plaques seen on chest radiographs. Pleural plaques are common in patients who have been exposed to asbestos, are asymptomatic and are most useful as a marker of asbestos exposure or asbestosis. They can be identified in 3-14% of dockyard workers and in 58% in insulation workers.

They are themselves not malignant, but patients with this plaques have a greater risk of mesothelioma and bronchogenic cancer than the general population and patients with exposed to asbestos but not pleural plaques.

The plaques arise in the parietal pleura and have predilection for the diaphragmatic dome and the undersurface of the lower posterolateral ribs. Rarely involve the visceral pleura but occasionally they are found in the fissures of the lungs.

On plain radiographic plaques appear as a geographic, usually calcified, opacities with irregular but well-defined edges. The irregular thickened nodular edges of the pleural plaques are likened to appearance of a Holly leaf, which has sharp spines along its margin.

Sources:

1. Jane R, Gulati A., Dwivedi R., Avula S., Curtis J., Abernethy L. (2013) We wish you a Merry X-Ray-mas: Christmas signs in radiology. BMJ 347:f7020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7020

2. Walker C., Takasugi J., Chung J., Reddy, G., Done S., Pipavath S., Schmidt R., Godwin J. (2012). Tumor-like Conditions of the Pleura. Radiographics 32:971–985.

3. Case radiograph courtesy of Dr Çağlayan Çakır, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 22986

Figure below. Ilex aquifolium. Courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 12398

Holly leaf sign.

Click on the image for a larger depiction

Article submitted by: Prof. Claudio R. Molina, MsC.

- Details

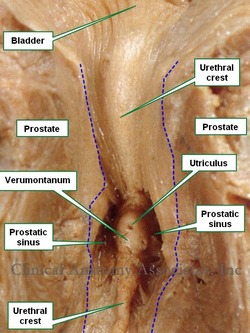

Anterior view of a section of the prostate gland. The blue

dotted line shows the edges of the prostatic urethra

[UPDATED] The [prostatic utricle], also known as "utriculus prostaticus" or "utriculus" is a small 6 mm small dead-end channel found in the male prostatic urethra.

The word [utriculus] is Latin and means "little sac"..

What is interesting about this structure is that it is the embryological remnant in the male of the Müllerian ducts that form the vagina and the uterus in the female. In fact, in some texts the prostatic utricle is referred to as "uterus masculinus". Some researchers differ and point to the fact that this structure may not be a Müllerian duct derivate.

The prostatic utricle is found inside the prostate, forming part of the posterior wall of the prostatic urethra. It is in the upper part of a small mound which is part of the prostatic crest. This mound is called the [colliculus seminalis] or [verumontanum], which is Latin and translates as the "mountain or mound of truth". On the verumontanum are the two slit-like openings of the ejaculatory ducts. Lateral to the verumontanum are the prostatic sinuses, depressions where the prostatic ducts are found.

Sources:

1. "The prostatic utricle is not a M?llerian duct remnant: immunohistochemical evidence for a distinct urogenital sinus origin" Shapiro E, Huang H, McFadden DE, et al. (2004) J Urol 172; 1753–1756

2. "Gray's Anatomy"38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

3. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Jane Todd Crawford - Daguerrotype

When writing the article “The Ephraim McDowell House and Museum” I realized that there are so many patients that by volunteering to a novel or sometimes experimental procedure or donating their bodies have been the catalyst of the advancement of medical science, surgery, and anatomy. Benigno says it so clearly in his paper explaining the physician/patient relation of McDowell and his patient: “Because of his innovative genius and finally honed surgical skills, Ephraim McDowell gave Jane Todd Crawford her life, and she, in return, gave him immortality”.

Few patients have influenced local history more than Jane Todd Crawford. In Kentucky there is a road named after her, a hospital bears her name in Greenville, KY, and there is even a formal "Jane Todd Crawford Day" on December 13!

By contrast, there are so many unknown patients whose names history has forgotten, and yet the fame of the physician continues through time in eponymic hospitals, educational institutions, named surgical procedures or maneuvers, surgical instruments, etc.

Some of the names and stories have survived, but many have not. In some cases, we know the name, but little else.

Dr. Henry Heimlich used his “Heimlich maneuver” for the first time to save his neighbor Patty Ris, in 2016, forty-two years after publishing it in 1974. The maneuver itself was used that same year (1974) to save the first person, Irene Bogachus, who was choking at a restaurant. Hundreds of thousands of people have been saved from death from choking by the proper use of this maneuver.

Dr. Christiaan Barnard, performed the first successful heart transplant on December 3, 1967. We know the name of the donor, 25 year-old Denise Darvall, and the recipient Lewis Washkansky.

Dr. Antoine Dubois and Dr. Dominique-Jean Larrey in France performed the first mastectomy on September 30, 1811. This was decades before the advent of anesthesia or aseptic technique. The patients was Fanny Burney, a famous novelist.

Dr. Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine after working with a milkmaid, Sarah Nelmes. Jenner’s work saved the Americas from the smallpox epidemic through the work of Don Antonio de Gimbernat y Arbós and Don Francisco Javier de Balmis i Berenguer and his “Balmis Expedition”

The examples can continue, but who was the patient on the first Billroth procedure, who was the patient in the first Scopinaro procedure? Who was the patient on whom Dr. Eric Muhe performed the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Many are unknown yet they helped pave the way of the future.

The same can be said for the world of human anatomy. Today we honor the donors who will their bodies so that future physicians can study the intricacy of the human body, but we never know their names or their stories. Many a time I have stood at the side of a body while medical students dissect and study and wondered about their identities, the life they had, and what led them to give us their bodies as a wonderful gift to science and medicine.

There was a time (long ago) when the dissection of a human body was punished by the Church, or the times when the scarcity of bodies was such that some started to rob graves, or when the punishment for a crime was “death and a public anatomy”.

Some of these people we know, most of them we do not. Some have given their body willingly, others have not.

Joseph Paul Jernigan, a murderer, who after given the death penalty, donated his body to a now world-renown endeavor, the Visible Human Project.

The oldest known anatomical preparation is a skeleton mounted in Basel (Belgium) by Andreas Vesalius in 1543. The skeleton belongs to Jacob Karrer von Geweiler, a bigamist and attempted murderer who was beheaded for his crimes.

It is sad that we know the names of these criminals, and in some cases not that of their victims.

We do not know the names of many who, during the Nazi regime in WWII, were taken from concentration camps for medical experiments and as we understand, possibly murdered and dissected to illustrate now infamous anatomical atlases. Research is being done to discover their identities.

Times have changed and body donation has become accepted and praised by society. I am always touched by the words of Morgagni above the entrance to the dissection rooms at the University of Cincinnati: “hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae” meaning “in this place death rejoices helping the living”. The University of Cincinnati has an Annual Memorial Ceremony to honor the body donors and their families. A video of the ceremony can be watched here.

I cannot but end this article with the words that are found in the left side column of this blog and will always be there:

“Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Susan C. Potter

Image capture from a video

The title of this article is a reference to another article in this blog: “The unknown patient / donor” which honors all those who have anonymously donated their bodies to further the anatomical training of many in the medical field. They trusted that those who would use their bodies would do so ethically and with respect, but they did not know exactly how they were to be used or what was going to be done with their bodies.

Susan Potter was the exact opposite. She knew that her body was going to be coated with polyvinyl alcohol, frozen, cut into four pieces with a huge handsaw, and then it would be ground or milled into 27,000 slices of 63 microns each, which were to be photographed in exquisite detail.

She offered her body to science and spoke with Dr. Vic Spitzer, who had directed the Visible Human Project, the first digital cadaver in 1994. She agreed to the donation, but only after she had toured the facilities and only after she clearly understood what was going to her body and why.

The why is the most interesting part of her story. Susan had a very interesting medical history, including spinal surgery , double mastectomy, and a hip replacement. Normally her body would have been rejected, but doctors see this type of patients in their practices. Patients who are old, frail, with prior surgeries and a multitude of problems. This is why she was chosen

If images are needed, usually cadavers are scanned and imaged postmortem, but in her case, Susan underwent many imaging studies while she was alive. She was interviewed and filmed countless times so that her videos would be added to the digital cadaver that was going to be made of her, becoming de facto, a digital patient.

Susan donated her body in the year 2000 died of pneumonia in 2015. During those 15 years she became a friend of Dr. Spitzer, gave talks to medical students, and collaborated with this project.

National Geographic followed Susan for these 15 years and documented her life and death. You can read her story here or watch the video in this article. The development of the software continues. I am sure we will hear more from Susan Potter's contributions long after her death.

NOTE: My thanks to our contributor Pascalle Pollier for bringing Susan Potter to my attention. Dr. Miranda

“Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

- Details

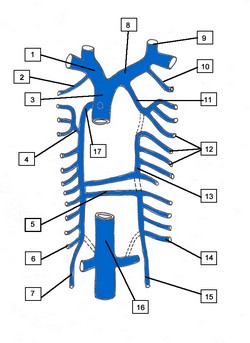

The azygos venous system drains the posterior aspect of the thorax via the posterior intercostal veins It also connects the vascular territories of the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and is the superior continuation of the lumbar veins. The azygos system was first described by Bartolomeo Eustachius (c1500 - 1574).

The name azygos comes from the Greek [ζεύγος] and means “unyoked” or better “asymmetrical”. This system is different on each side of the body, also having important anatomical variations.

The azygos vein (Lat: vena azygos major) is the larger vein of the azygos system and is found on the right side of the body. It begins at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra as a continuation of the right ascending lumbar vein; sometimes by a branch from the right renal vein or from the inferior vena cava. It enters the thoracic cavity through the aortic hiatus of the respiratory diaphragm, and ascends along the right side of the vertebral column to level of the fourth thoracic vertebra, where it arches forward over the root of the right lung, at this point the vein is called the azygos arch, which terminates in the posterior aspect of the superior vena cava (SVC) just superior to the point where the SVC enters the pericardium.

In the thorax, the azygos vein is found to the right of the thoracic duct on the right side of the descending aorta; it lies upon the intercostal arteries and is partly covered by the parietal pleura.

The azygos vein receives the right subcostal vein, nine or ten right posterior intercostal veins, the hemiazygos vein, the accessory hemiazygos vein, the right superior intercostal vein, and several minor esophageal, mediastinal, and pericardial veins.

The left side of this system is more complex and presents with more anatomical variations. Its main component is the hemiazygos vein (Lat: vena azygos minor), also known as the left lower azygos vein. It is a continuation of the left ascending lumbar vein, and it sometimes may arise from the left renal vein and passes into the thorax usually through the left aortic crus of the respiratory diaphragm. It ascends to the level of the 7th or 8th thoracic vertebra where it crosses the midline posterior to the esophagus, descending aorta and thoracic duct to empty into the right-sided azygos vein. It receives the left subcostal vein and three to four lower posterior intercostal veins, and some esophageal and mediastinal veins.

The second component of the left azygos system is the accessory hemiazygos vein, also known as the left upper hemiazygos. This component varies in size depending on the third venous drainage component of the left posterior thoracic wall. This is the left superior intercostal vein (see attached diagram).

The accessory hemiazygos, similar to the hemiazygos vein will cross the midline posterior to the esophagus, descending aorta and thoracic duct to empty into the right-sided azygos vein. It may do so by a common vein or by a separate vein as shown in the attached diagram. If there is a common vein the hemiazygos is considered to be the inferior component and the hemiazygos is considered to be the superior component.

The left superior intercostal vein receives three or four posterior intercostal veins, and empties into the left brachiocephalic vein. In rare cases of absence of the hemiazygos vein, this left superior intercostal vein will extend as low as the fifth or sixth intercostal space.

Although not considered to be part of the azygos system, the drainage of the posterior thoracic wall is completed by the right and left supreme intercostal veins which empty the posterior aspect of the first intercostal space into the left and right brachiocephalic veins respectively.

The azygos system of veins constitute an important collateral venous circulation pathway which can be seen in action in cases of blockage of the superior or inferior vena cavæ.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

4. "Reconstructive Anatomy: A Method for the Study of Human Structure: Arnold, M WB Saunders1968

Image modified from the original from Arnold (4)