This article is coauthored by Randall K. Wolf, MD and Efrain A. Miranda, PhD

Can there exist a unified theory that deciphers the mechanisms for cardiac arrythmias and atrial fibrillation (AFib) that can also explain the results of various catheter-based and surgical-based treatments? Based on anatomical and physiological study of the heart and it’s nervous system, we believe the answer is yes.

While we have learned not to expect everyone to be persuaded by the argument we will be presenting, we suggest, nevertheless, this argument does deserve careful and dispassionate consideration for it provides a model which explains results in the treatment of AFib, and should not be ignored. The epiphany that shed light on a possible unifying mechanism came during multiple cases of left atrial electrical testing during minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) in patients who had multiple previous catheter-based PVI ablation procedures.

Over the years we have evolved our view of the anatomical structures and processes that control the beating rhythmic activity of the heart. Additional and complementary information can be found following the links in the article.

First, we need to define two terms in reference to the heart: “Intrinsic” and “Extrinsic”. An intrinsic structure is found within the boundaries of the heart, that is, within the parietal pericardium. Extrinsic means that the structure about is found outside the parietal pericardium.

The most well-known intrinsic component is what we know as “the conduction system of the heart”. The classic description of the conduction system of the heart emphasizes this cardiomyocyte- based component and refers to a group of specialized cardiac muscle structures that serve as pacemakers and distributors of the electrical stimuli that make the heart beat coordinately. It is important to stress the fact that this primary "conduction system of the heart" is not formed by nerves, but rather by specialized cardiac muscle cells. Probably the reason so much emphasis is placed on the conduction system of the heart is the use of the electrocardiogram as a clinical diagnostic tool since William Einthoven (1860 - 1927) introduced the EKG in 1901.

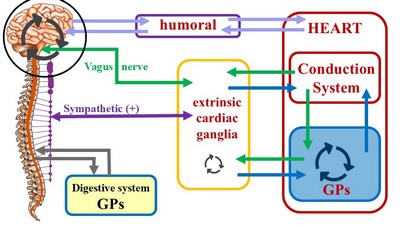

The second (quite complex) component of this system has been forced to take a secondary place, and in many cases ignored. We refer to the modulating activity on the heart by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), with its two subsystems, sympathetic and parasympathetic.

Unlike the conduction system of heart, which is purely intrinsic, the cardiac autonomic system is both extrinsic and intrinsic. The classic architecture described is a two-neuron system, where an extrinsic preganglionic neuron located in the central nervous system (CNS) connects with an extrinsic postganglionic neuron found in the sympathetic chain and ganglia located in the superficial and deep cardiac plexuses close to the aorta and pulmonary trunk.

The cardiac ANS has an intrinsic component formed by ganglionated plexi (GPs) and nerves found within the walls of the myocardium and in epicardial areas of the heart which contain fat. The main location of these GPs is close to and around the great vessels. These ganglionated plexi are the basis for the complex rhythmicity responses of the hear. In fact, several researchers call these intracardiac plexuses the "Little Brain of the Heart". Failure of the ganglionated plexi are the basis of many cardiac arrythmias, including atrial fibrillation.

The inclusion of the cardiac ganglionated plexi into this picture has led us to propose a different ANS organization for those organs that have rhythmicity, be it a beat (heart) or peristalsis (digestive system, ureters, urethra, etc.). For a more detailed explanation follow this link to another article on this topic.

These cardiac intrinsic ANS component are responsible for the complex reflexes that increase or decrease both the heartbeat and the force of contraction of the heart muscle in response to variations in volumetric pressure in the atria and chemical variations in the blood caused by alcohol, caffeine, drugs, dehydration, etc. A more detailed explanation can be found in the following Houston Methodist DeBakey CV Live video. Click on the video to start it or you can go directly to YouTube by clicking here. The main content start at 2 minutes:

The cardiac ANS has important communication with the brain centers responsible for mood and emotions. It is important to note that emotional response is linked to visceral activity (glands and viscera), and this includes the heart.

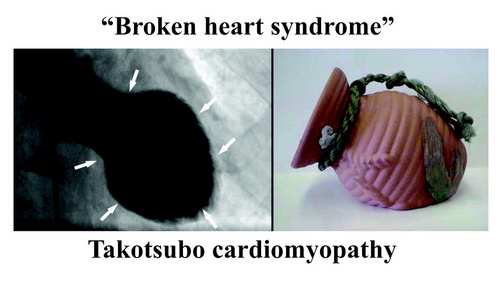

Also, the ANS/GPs complex is not separated from the higher functions of the forebrain. Cechetto (2005) explains how the forebrain (conscious) activity influences the spinal cord and the ANS by pathways that include the limbic system, insula, amygdala, and lateral hypothalamus. These pathways and communications can certainly explain arrythmias caused by stress and anxiety and pathologies such as the “broken heart syndrome” (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy).

Note: "Broken heart syndrome" or "stress cardiomyopathy" is also known as "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy". This is because the shape of the heart in this condition changes and resemble a Japanese octopus (tako) trap (tsubo). For more information on this condition, click here.

Sources and references

1. Kawashima, T. The autonomic nervous system of the human heart with special reference to its origin, course, and peripheral distribution. Anat Embryol (2005) 209: 425–438

2. D. F. Cechetto, "Forebrain Control of Healthy and Diseased Hearts," Chapter in "Basic and Clinical Neurocardiology", J. Armour and J. L. Ardell, Eds., Oxford University Press, 2004.

3. Kandel ER, Koester JD, Mack SH, Siegelbaum SA. Principles of Neural Science. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2021.

4. Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 42nd ed. London, UK: Elsevier; 2021.

5. Haines DE, Mihailoff GA. Fundamental Neuroscience for Basic and Clinical Applications. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

6. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

7. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al. Neuroscience. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018.

8. Felten DL, Maida MS. Netter’s Atlas of Neuroscience. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

9. Wolf, RK; Miranda, EA. Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: A New Look at an Old Problem. 2024 Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

10. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Harvard.edu