Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 4484 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

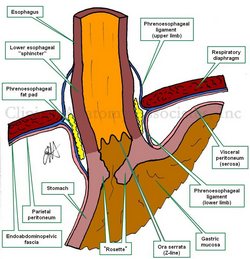

The esophagogastric junction is a complex anatomical region found at the esophageal hiatus of the respiratory diaphragm. It allows passage of he esophagus from the thorax into the abdomen.

The hiatus is bound by two muscular crura, both of which arise from the right tendinous aortic crus. Since the intraabdominal pressure is higher than the intrathoracic pressure, there is a series of structures at the phrenoesophagogastric junction to close the esophageal hiatus.

The infradiaphragmatic parietal peritoneum reflects off the diaphragm towards the stomach to form its serosa layer (visceral peritoneum). At the same time the infradiaphragmatic fascia, also known as the endoabdominopelvic fascia, splits into two components or limbs. These are the superior and inferior phrenoesophageal ligaments or phrenoesophageal membranes. (the root [-phren-] means "diaphragm"). These phrenoesophageal ligaments create a disc-like plug between the abdomen and the thorax. This "plug" is reinforced by a circular infradiaphragmatic fat pad. The phrenoesophageal ligaments are reinforced on their thoracic aspect by the endothoracic fascia.

The lower esophagus has a dilation (evident in the image) called the "esophageal ampulla", in relation to this dilation the circular muscle layer of the esophagus slightly thickens creating the so-called "lower esophageal sphincter". This area is not a true anatomical sphincter, but rather is a functional sphincter.

The esophagogastric mucosal junction shows a marked transition in the shape of a wavy line. This is called the Z-line or the ora serrata. Extensions of the gastric mucosa and submucosa inferior to the ora serrata create a valve-like flap called the "gastroesophageal flap valve". When viewing this mucosal flap through and endoscope, it looks corrugated and flower-like, hence it is also called the "rosette".

The congenital or pathological dilation of the esophageal hiatus can predispose to esophageal hiatus hernia.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Original image by Dr. E. Miranda

- Details

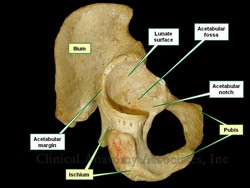

The word acetabulum is formed by the combination of the Latin root [acetum], meaning "vinegar", and the Latin suffix [-abulum] a diminutive of [abrum], meaning a "cup", "holder", or "receptacle". Thus formed, the word acetabulum means "a small vinegar cup".

Roman soldiers liked to drink their water mixed with a small quantity of vinegar, so as to reduce the sensation of thirst. This mix was called "Posca". An acetabulum was used to add specific quantities of vinegar to the water, so over time the acetabula (plural form of acetabulum) were considered measuring devices. It is said that they measured one cup, or 2 1/2 oz. of wine.

The anatomical acetabula are bilateral cup-like depressions in the os coxae which serve as a component of the coxofemoral joint (hip joint). They are found at the intersection of the three bony components of the os coxae, the ilium, ischium, and pubic bone and look anteroinferiorly.

The acetabulum has several components:

• Acetabular margin: An incomplete circular bony edge or border that marks the edge of the acetabulum

• Acetabular notch: The area where the acetabular margin is incomplete

• Acetabular labrum: Labrum (Lat. :lip). The acetabular labrum is a complete circular ring of fibrocartilage found on the acetabular margin that helps maintain the head of the femur in place. It is not shown in the accompanying image

• Lunate surface: A smooth, half-moon shaped area on the floor of the acetabulum. It is covered with hyaline cartilage and allows for articulation with the head of the femur

• Acetabular fossa: The non-articular region of the floor of the acetabulum. It contains fat, vessels, and the ligament of the head of the femur

Interesting fact: You may find that in older English anatomy books the acetabulum is referred to as the cotyloid cavity. The word cotyloid arises from the Greek [κοτυλοειδές] and means "similar to a cup". This separation in terms still exists when studying anatomy in other languages. For example, in Spanish the acetabulum is called "cavidad cotiloídea" or "cotilo", and in French it is called "cavité cotyloïde" or "cotyle". I guess the Greek soldiers did not drink vinegar with their water...

Image property of: CAA, Inc. Photographer: David M. Klein

- Details

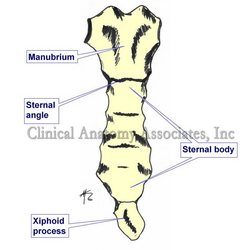

UPDATED:The sternal angle is the term used to denote the angulation at the joint between the manubrium and the body of the sternum. This transverse joint is called the "manubriosternal joint" and is a secondary cartilaginous joint of a type known as a symphysis. The angle varies between 160 and 169 degrees.

It is know eponymously as the "angle of Louis" named after Antoine Louis1 (1723-1792), a French physician. The importance of the sternal angle is that of an anatomical superficial landmark, which forms a horizontal plane which indicates a series of anatomical occurrences, as follows:

• Location of the cartilages of the second rib

• Beginning and end of the aortic arch

• Boundary between the inferior and superior mediastinum

• Location of the bifurcation of the trachea

• Posteriorly, the plane of the sternal angle passes trough the T4-T5 intervertebral disc (sometimes a little lower, through the superior aspect of T5)

• Highest point of the pericardial sac.

• It is the point where the right and left pleurae meet in the midline. They touch, but their pleural spaces do not communicate (usually).

1. Some authors contest the eponym, adjudicating it to Pierre Charles Alexander Louis (1787-1872), another French physician.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.. Artist: David M. Klein

Thoracic anatomy, pathology and surgery, are some of the many lecture topics developed and presented by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. For more information Contact Us.

- Details

- Written by: Pascale Pollier

Cover of the book by Theo Dirix

My partner in crime and fellow traveler, Theo Dirix, has just published a new account of our common quest for the lost grave of Andreas Vesalius. Until the scientific results of our latest mission in Zakynthos in September 2017, will become public, this collection of articles published since 2014 represents a detailed and complete status quaestionis of a search that will never be the same anymore.

I'm proud and grateful to be part of a team he describes a most tenacious.

Following is a remarkable quote from the book: "The beast you have in your hands may appear as aged and stubborn: indeed, the texts collected here are not new and they regularly echo each other. The beast barks and growls: these words do not intend to examine or research but were meant to sell a project to potential sponsors. I feel the taste of the creature’s spit in my face, but pleading not guilty to any accusation of self-glorification, I do hope I managed to teach it a few tricks you will enjoy. While continuing to write about Vesalius’s death and his grave, black dogs may still be scratching at my hermitage. When I will finally throw open the doors to the beauty beyond, here’s hoping the encounter with the female spider will taste as fresh as a first kiss and be the beginning of something else."

No surprise some have described the book as: "a truly captivating story (a Live Adventure!) written in a fascinating, passionate and inspiring way. Theo Dirix, with his unique style is describing facts from his adventure to locate the grave of Vesalius and he is mentioning with great respect all his collaborators, the friends of Vesalius and those who share the same passion for Anatomy and Art." (Vasia Hatzi on Med in Art).

The book can be ordered here: https://www.shopmybooks.com/US/en/book/theo-dirix-32/in-search-of-andreas-vesalius. (English version of the website). More information about the author on his website www.theodirix.com. or here.

Personal note: Thanks to Pascale Pollier, a contributor to this website, for allowing us to publish this article, originally published on Vesalius Continuum.

I received a personalized copy from the author, Theo Dirix; Thank you very much for the recognition and the use of this website as reference in some of your comments. It is a great read for anyone even mildly interested in the life and specially the death and disappearance of the grave of Andreas Vesalius. There are several passages in the book that I will have to research and transform in articles for this blog.

For those who collaborated in the GoFundMe campaign because or our article entitled Do you want your name in a book? The Quest for the Lost Grave.... this is the book and the name of all the contributors are listed in it!

The quest continues... Dr. Miranda

- Details

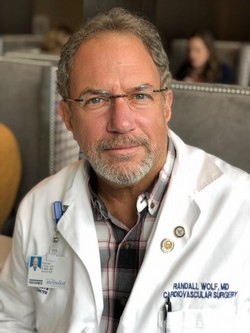

- Written by: Randall K. Wolf, MD.

If you arrived to this article looking for information on Atrial Fibrillation, you will find some in this article. If you need to contact Dr. Wolf, please click here.

Dr. Randall K. Wolf

Dr. Randall K. Wolf

HOUSTON AFib PATIENT EXPERIENCE SEMINAR

Saturday, April 21st, 2018 9am – 4pm

Westin at Memorial City, 945 Gesner Rd.

Houston, TX 77024

877-900-AFIB (2342)

This seminar is free and open to the public. To attend, please call the telephone number to register.

WELCOME MESSAGE FROM DR. RANDALL WOLF

In my experience over the last 18 years as a physician who specializes in the treatment of Atrial fibrillation (AFib), I have learned AFib sufferers want two things: Hope and a chance to feel better.

The first step to hope and to feeling better is to self educate. Learn about the latest medications, techniques and devices to treat AFib. Ask questions. Get a second opinion. Take charge of your health.

The purpose of the Houston AFib Patient Experience Seminar is to help AFib sufferers like you take charge of your health.

About 30 million people worldwide carry an AFib diagnosis. Today seems everyone either has AFib or knows someone that has AFib. When I first held an Afib seminar in Beijing, China, over 1200 people with AFib signed up for the seminar. It was standing room only!

Despite the common occurrence of AFib around the world, a recent study found that in patients who were diagnosed with AFib, 40-50% of patients with an elevated risk of stroke were not treated with the best therapy, and the rate of stroke over the next five years was 10%.

Here in Houston, we can do better! Learn more about AFib right here today, and I guarantee you will have hope and be more likely to reach your goal of feeling better.

Towards an AFib free healthy life,

Randall K. Wolf, MD.

ABOUT THE HOUSTON AFIB PATIENT EXPERIENCE SEMINAR

The University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery Department in Houston, is proud to host the inaugural Houston AFIB Patient Experience Seminar. The purpose is to educate the public in an interactive format allowing the audience to engage in conversation in a question/answer format with leading medical professionals. Our list of panel members and guest presentations include surgeons, cardiologists, neurologists, pulmonologists as well as testimonials from AFib patients. We are honored to be able to bring awareness to the resources and options available to patients suffering from AFIB.

NOTE: If you cannot attend the seminar, there is more information on Atrial Fibrillation at this website; click here.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

This article continues the musings of "Interesting discoveries in a medical book". In this book I found a copy of a letter written by Ephraim McDowell, MD; who on December 25, 1809 performed the first recorded ovariotomy in the world. The patient was Mrs. Jane Todd Crawford, who has also been the subject of several articles in this website, including a homage to the "unknown patient/donor".

The book belonged to Cecil Striker, MD, who practiced in Cincinnati. Dr. Striker was a faculty at the University of Cincinnati and one of the founders of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). He also was one of the first physicians to work in 1923 with a "newly discovered" drug by the Eli Lilly Company (Indianapolis) this drug was named Insulin. The medical application of Insulin had only just been discovered about a year earlier.

Inside the book there is a copy of a letter by Dr. Ephraim McDowell to Dr. Robert Thompson dated January 2nd, 1829, a year before Dr. McDowell's death. At the time (1829) Dr. Thompson (Sr.) was a medical student in Philadelphia. According to the note Dr. Thompson lived in Woodford County, KY, had three children and died in 1887. One of his children was also a doctor, but I have not been able to ascertain if this book was given to him by Dr. Striker.

Inside the book there is a copy of a letter by Dr. Ephraim McDowell to Dr. Robert Thompson dated January 2nd, 1829, a year before Dr. McDowell's death. At the time (1829) Dr. Thompson (Sr.) was a medical student in Philadelphia. According to the note Dr. Thompson lived in Woodford County, KY, had three children and died in 1887. One of his children was also a doctor, but I have not been able to ascertain if this book was given to him by Dr. Striker.

The letter is shown in the image attached. In this letter Dr. McDowell describes in his own words the ovariotomy he performed on Jane Todd. He also describes other ovariotomies he performed and his opinion on "peritoneal inflammation".

Note how the letter has no paragraph separation. Apparently, at the time writing paper was expensive and the less pages used, the better! The text of the letter is as follows:

Danville, January 2, 1829

Mr. Robert Thompson

Student of Medicine

No. 59 Spruce Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Sir,

At the request of your father I take the liberty of addressing you a letter giving you a short account of the circumstances which lead to the first operation for diseased ovaria. I was sent in 1809 to deliver a Mrs. Crawford near Greentown of twins; as the two attending physicians supposed. Upon examination per vaginam I soon ascertained that she was not pregnant; but had a large tumor in the abdomen which moved easily from side to side. I told the lady that I could do her no good and carefully stated to her, her deplorable situation. Informed her that John Bell, Hunter, Hay, and A. Wood four of the first and most eminent surgeons in England and Scotland had uniformly declared in their lectures that such was the danger of peritoneal inflammation, that opening the abdomen to extract the tumor was inevitable death. But not standing with this, if she thought herself prepared to die, I would take the lump from her if she would come to Danville. She came in a few days after my return home and in six days I opened her side and extracted one of the ovaria which from its diseased and enlarged state weighed upwards of twenty pounds. The intestines as soon as an opening was made run out upon the table, remained out about twenty minutes and being upon Christmas Day they became so cold that I thought proper to bathe them in tepid water previous to my replacing them; I then returned them, stitched up the wound and she was perfectly well in 25 days. Since that time I have operated eleven times and have lost but one. I now can tell at once when relief can be obtained by an examination of the tumor if it floats freely from side to side or appears free from attachments except of the lower part of the abdomen. I advise the operation, having no fear from the inflammation that may ensue. I last spring operated upon a Mrs. Bryant from the mouth of the Elkhorn from below Frankfort. I opened the abdomen from the umbilicus to the pubis and extracted sixteen pounds. The said contained the most offensive water I ever smelt, and the attendants puked or discharged except myself. She is now living; from being successful in the above operation. Several young gentlemen with ruptures have come to me. I have uniformly cut the ring open, put the intestines up if down the cut the ring all around, every quarter of an inch then pushed the parts closely together and in every case the cure has been perfect. Therefore it appears to me a mere humbug about the danger of the peritoneal inflammation. Much talked about by most surgeons. After wishing you Health and Happiness,

I am yours sincerely

E. McDowell

P.S. Your father looks better than I have ever seen. Your sister is also in health

The most important point of this letter is how easily and publicly they name patients and their home addresses. Today this would be a violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, commonly known as HIPPA, a legislation that provides data privacy and security provisions to safeguard patient medical information.

It is also interesting to see how Dr. McDowell explained to Mrs. Crawford how difficult and dangerous the procedure would be. He stated how four renown surgeons in England and Scotland said that opening the abdomen was "inevitable death". Another point was how long the intestines were outside the body ... twenty minutes, and the maneuver Dr. McDowell used to bring them back to normal temperature. Late December in Kentucky is quite cold, even with wooden stoves and such. I wonder how much the lower temperature helped the patient.

The last point refers to his success in hernia procedures in young males. In the 1800's the word "rupture" was the standard to name abdominal hernias. Without explaining the procedure in detail, Dr. McDowell says that "every cure has been perfect". At the time, this was unprecedented, as the recurrence of inguinal hernia procedures, when attempted, was close to 25%.

The house where Dr. McDowell lived and practiced is today a museum in Danville, KY. In February, 2017 I visited this museum and wrote an extensive article on it. I encourage those interested in the History of Medicine to visit the place.