Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 177 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

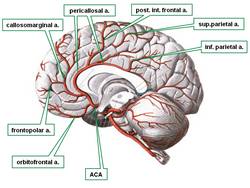

The anterior cerebral arteries are one of the two paired terminal branches of the internal carotid artery. Each anterior cerebral artery supplies arterial blood to the brain beyond the arterial circle of Willis. The vascular territory of the anterior cerebral artery supplies the medial surfaces of the frontal and parietal cerebral lobes as well as the medial border of the same lobes.

The anterior cerebral artery gives off the orbitofrontal artery and then divides into two callosal arteries, the pericallosal artery and the callosomarginal artery. From these arteries arise all the other branches that form the vascular territory of the anterior cerebral artery.

There are many anatomical variations of the anterior cerebral artery, as described here.

Clinical anatomy, pathology, and surgery of the brain and spinal cord are some of the lecture topics developed and delivered by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc.

Image modified from the original (in the public domain) by Sobotta (1945)

- Details

The medical term thrombus arises from the Greek [θρόμβος] (pronounced thrombos) meaning "a lump", "a piece of milk curd", or a "clot". This Greek term was later adopted in Latin [thrombus] and is used in this unchanged form today. The plural for thrombus is [thrombi]. A synonymous Latin term is [coagulum] (pl. coagula).

In medicine, a thrombus is a blood clot that has the connotation of being stationary, fixed to a vessel wall. If this blood clot were to be freed and start moving with the blood flow, then the clot should be called an "embolus" (Lat; pl. emboli).

Because of its anatomical characteristics. in the presence of atrial fibrillation, the left atrial appendage is particularly prone to the formation of thrombi, which can embolize and cause brain strokes.

The root term for this word is [-thromb-]. Examples of its use are:

- Thrombosis: The suffix [-osis] means "condition" with the connotation of "many". A condition of multiple thrombi

- Thrombocytopenia: A combination of root terms; the root term [-cyt-] means "cell" and the suffix [-(o)penia] means "a deficiency". A deficiency of platelets (the "clotting" cells)

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

- Details

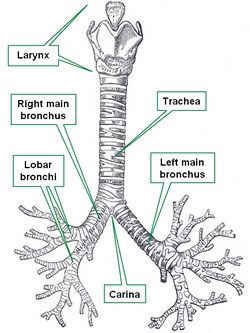

The trachea, vernacularly known as the "windpipe", is in the adult a 4 inch (10.1 cm) membranous tube which contains incomplete, almost circular rings of cartilage. Some authors describe between fourteen to sixteen of these incomplete rings of cartilage in the trachea.

These semicircular rings are open-ended posteriorly, where the trachea only has a membrane, thus being flattened posteriorly. This posterior aspect of the trachea is in close anatomical relationship with the thoracic esophagus.

The trachea begins at the inferior end of the larynx, just about the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, and descends in the superior mediastinum to the level of the sternal angle (of Louis) close to the superior border of the fifth thoracic vertebra, where it divides into two main bronchi, each entering the ipsilateral lung at the level of the pulmonary hilum.

The word [trachea] arises from the Greek [trakhus] meaning "rough". This is because in the original description of this structure there was the belief that all arteries were full of air (Lat. air = ar/aria). The trachea, being rough was called the "rough artery" or "tracheartery", which was later amended, eliminating the "artery" part. In Latin the term used for the trachea was [arteria aspera], also meaning "rough artery".

The internal lower border of the bifurcation of the trachea into the left and right main bronchi is knows as the carina, where the carinal lymphatic nodes are found.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

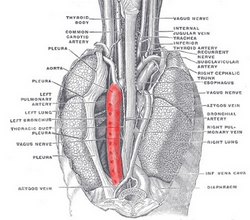

Posterior view of the contents of the thoracic cavity.

The descending aorta, also known as the thoracic aorta is the third portion of the aorta. It is found distal to the aortic arch in the posterior portion of the inferior mediastinum, and proximal to the abdominal aorta.

The descending aorta is situated between the lungs and has a close relation with the thoracic esophagus and the thoracic duct.

The descending aorta gives off 10 pairs of posterior intercostal arteries. The first intercostal artery, known as the supreme intercostal artery arises as a branch of the costocervical trunk of the subclavian artery. The last pair of arteries to arise from the descending aorta are the subcostal arteries, which pass under the 12th rib. The descending aorta also gives a number of smaller branches to the esophagus and the main stem bronchi.

The descending aorta ends at the aortic hiatus, where it continues as the abdominal aorta.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

First used by Galen of Pergamon (129AD - 200AD) the word [etiology] is of Greek origin. [αiτία] or [aitia], meaning "cause" or "reason", and [λογία] or [-ology], meaning "study of". Etiology is the "study of cause". In medicine this word is used to denote the study of the causes for a pathology, disease, or condition.

Because of its Greek origin, Skinner (1970) states that the proper way of spelling this term should be aetiology, but the initial "a" has been discarded through use.

There are many pathologies of unknown origin. In this case the word to use would be [idiopathic] or [idiopathy] meaning "of unknown cause"

- Details

The suffix [-(o)cele] arises from the Greek [κήλη] meaning "dilation" or "pouching". In medical terminology this suffix is used to mean "hernia", "bulging", or a "dilation". In older times a synonym was used for hernia: "rupture".

Dr. Aaron Ruhalter would state the proper description for an "ocele" is that of a prolapse, that is, a herniation without a hernia sac.

Examples the use of [ocele] are:

- Orchiocele: The prefix [orchi-] means "testicle" or "scrotum". Refers to a scrotal or testicular bulging, a scrotal hernia

- Hydrocele: The root term [-hydr-] means "water". A watery dilation. Usually used to refer to the accumulation of fluids in the scrotum

- Hydatidocele: Refers to a dilated cyst containing hydatids, the larval form of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus or Echinococcus multilocularis

- Enterocele: The root term [-enter-] means "intestine" or "small intestine". The bulging of the small intestine into the vagina because of weakness of the vaginal wall

- Cystocele: The root term [-cyst-] means "bladder" or "sac". The bulging of the urinary bladder into the vaginal canal because of weakness of the vaginal wall

- Cystourethrocele: A combination of root terms; [-cyst-] means "bladder" or "sac" and [-urethr-] means "urethra". The bulging of the urinary bladder and urethra into the vaginal canal

- Myelomeningocele: A combination of root terms; [-myel-] means "spinal cord" (also "bone marrow") and [-mening-] means "menynx". The herniation of the spinal cords and its meningeal coverings into the back, creating a bulge

- Varicocele: The root term [-varic-] means "varix" or "sac". A bulging of the skin caused by varices