Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1621 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

From the Greek [kheirurgia], a compound word meaning "a work done by hand". The Greek word [kheir/cheir] means "hand", and [ergon] means "work". The intent of the word is that of a medical treatment that is realized by the use of the hands and/or hand instrumentation.

Technology has advanced the evolution of surgery. Today minimally invasive surgical procedures, videoscopic procedures, and robotic-enhanced surgery are commonplace.

Images and links in the public domain, courtesy of:www.wikipedia.com

- Details

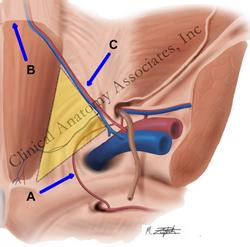

The arcuate line is the arch-shaped (hence the name) inferior border of the posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle. This structure is seen in a laparoscopic (posterior) view (see image, label "B") and represents the transition from a superior area with well-formed aponeurotic posterior rectus sheath to an area devoid of the posterior rectus sheath.

At this point, the inferior (deep) epigastric vessels (see image, label "C") pass from deep to superficial, under the arcuate line and continue superiorly providing blood to the rectus abdominis muscle.

The arcuate line also represents a transition from a well-formed and stronger wall posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle to a weaker region, covered only by deep muscle fascia and transversalis fascia. This allows a surgeon to enter the preperitoneal region using a Totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) approach for a laparoscopic herniorrhaphy.

Label "A" shows the "corona mortis" anatomical variation.

Image property of: CAA.Inc. Artist: M. Zuptich

- Details

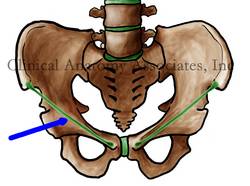

The inguinal (Poupart's) ligament has always been described as a separate, discrete, distinctive ligamentous structure. This is not so. The inguinal ligament is the thickened, incurved, lower free border of the external oblique aponeurosis. This structure extends between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) superolaterally, and the pubic tubercle inferomedially. The inferomedial portion of the inguinal ligament send fibers towars the pectineal ligament (Cooper's ligament) and forms the lacunar (Gimbernat's) ligament.

Inferior to the inguinal ligament is an open region (subinguinal space) that allows passage of structures between the abdominopelvic region and the femoral region. Some of these structures are: Iliacus muscle, psoas major muscle.

Although described by Vesalius, Fallopius, and others it was the French anatomist and surgeon Francois Poupart (1661-1708) who described this structure in relation to hernia in his book "Chirurgie Complete" published in 1695.

Image property of: CAA.Inc. Artist: D.M. Klein

- Details

The suffix [-itis] originates from the Greek and means "inflammation". This suffix is also used to mean "infection", although inflammation is only one of the signs of infection. The symptoms and signs of infection are:

- Edema - localized swelling (tumor)

- Redness- Localized (rubor)

- Localized raise in temperature - Fever (calor)

- Pain - (dolor)

- Localized functional impairment (functio lesa)

The terms in parentheses are the Latin words used to describe these symptoms and sign.

Examples of uses of this suffix are:

- Hepatitis: Inflammation or infection of the liver

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation or infection of the pancreas

- Cholecystitis: Inflammation or infection of the gallbladder [chole-]="gall'; [cyst]="sac" or "bladder"

- Rhinitis: Inflammation or infection of the nose

- Pharyngotracheitis: Inflammation or infection of the pharynx and trachea

- Details

The suffix [-oid] originates from the Greek [oeides], meaning "similar to", "like", or "shaped like". This suffix can be found the the medical terms [sigmoid] meaning "similar or shaped like a sigma"; [sphenoid], meaning "shaped like a wedge"; [cricoid], meaning "shaped like a ring", and [arytenoid] also from the Greek [arytaina], meaning "similar to a ladle".

This suffix is also used in daily conversation, as the following examples illustrate:

- Android - "similar to a human", from the Greek [andros] human

- Anthropoid - similar to a man, from the Greek [anthropos], "man"

- Asteroid - "similar to a star", from the Greek [aster], "star"

- Arachnoid - "similar to a spider", from the latin [arachnid], spider. It refers to the spider-web look of this menynx

- Details

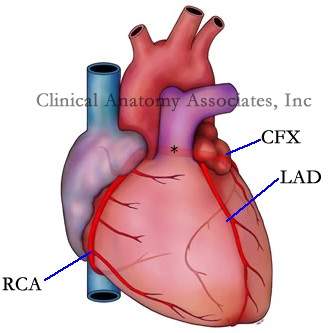

The term [coronary] comes from the Latin root [corona] meaning "crown", therefore [coronary] is used to denote a structure that surrounds another as a crown or a garland. In the heart, the coronary arteries and their branches form a crown that surrounds the heart at the level of the atrioventricular sulcus. There are two coronary arteries, which arises from, the root of the aorta; the right coronary artery (RCA), and the left coronary artery (*). The two main branches that arise from the left coronary artery are the circumflex artery (CFX) and the left anterior descending artery (LAD).

There can be interesting anatomical variations in the coronary arteries of the heart.

Although not in use anymore, the gastric arteries used to be called the "gastric coronaries" as the right and left gastric arteries and the right and left gastroepiploic arteries form a garland of arteries that surround the stomach. The term still does apply to the left gastric veins.