This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Giovanni Paolo Mascagni (1755-1815). Italian physician and anatomist whose meticulous research and illustrations revolutionized the understanding of the lymphatic system. Born in the mid-18th century, Mascagni's career spanned teaching, research, and political turbulence, culminating in posthumous publications that solidified his legacy. However, his work was marred by a posthumous scandal involving theft and plagiarism by his former assistant, Francesco Antommarchi.

Paolo Mascagni was born on January 25, 1755, in Pomarance (near Volterra), Italy, to Aurelio Mascagni and Elisabetta Burroni. Some accounts place his birthplace in the nearby village of Castelleto. He received his early education at home, focusing on philosophy, literature, physics, and mathematics, before enrolling at the University of Siena to study medicine. Mascagni graduated with a medical degree in 1777. He was appointed assistant prosector to the anatomist Pietro Tabarrani (1702 - 1779). Following Tabarrani's death, he succeeded him as anatomy lecturer at the University of Siena.

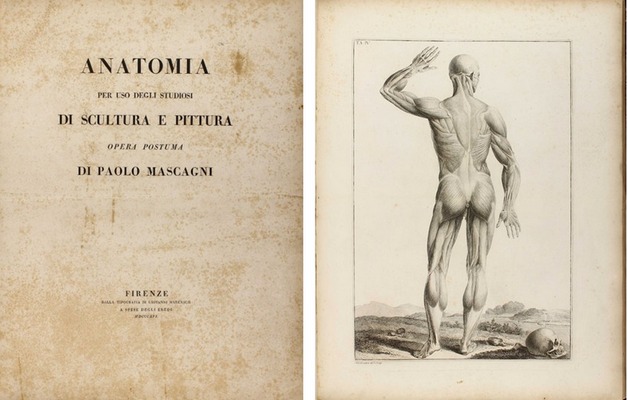

Mascagni's career was marked by academic accolades and political challenges. In 1796, he was elected a corresponding member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and in 1798, he became president of the “Accademia dei Fisiocritici”(see end notes) in Siena. His Jacobin sympathies during the French occupation of Tuscany in 1799 led to his appointment as superintendent of arts, sciences, and charitable institutions, but after the French were expelled, he faced arrest and seven months in prison. Freed by royal decree in 1801, Mascagni was appointed professor of anatomy at the University of Pisa and a lecturer at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. By 1807, he held the chair of anatomy at the University of Florence, where he also taught anatomy to artists, painters, and sculptors. As a result of his interest in human anatomy and art, the book “Anatomia per uso degli studiosi di scultura e pittura. Opera postuma” (Anatomy for the use of students of sculpture and painting) was published in 1816, one year after his death.

An accomplished artist himself, Mascagni collaborated with sculptor Clemente Susini (1754 – 1814) to create approximately 800 anatomical wax models, some of which are preserved in European museums: Museo La Specola, Florence, Italy; Museum Josephinum, Viena, Austria, etc. He also mentored Sardinian anatomist Francesco Antonio Boi (1767 – 1850), contributing to wax models now held in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Cagliari, Italy.

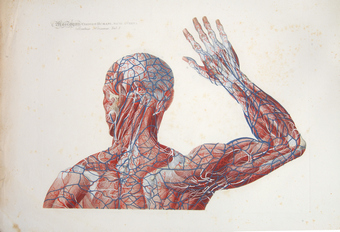

Mascagni's innovative techniques, such as injecting mercury into lymphatic vessels for visualization, allowed him to map a large part of the human lymphatic system, disproving earlier theories and highlighting its role in absorption and pathology. He is also credited with the early discovery of meningeal lymphatic vessels, later confirmed in modern studies (2014–2017). Mascagni died of sepsis on October 19, 1815, in Chiusdino, Italy.

Mascagni's publications blend scientific precision with artistic illustration. His 1784 work,” Prodrome d'un ouvrage sur le systeme des vaisseaux lymphatiques” (Initial notes on a work on the system of the lymphatic vessels), detailed his research on the lymphatic vessels and earned a prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences. This was followed by his 1787 publication “Vasorum lymphaticorum corporis humani historia et iconographia” (History and images of the lymphatic vessels of the human body), featuring 41 copperplates that provided the first complete description of the lymphatic system.

His most famous work was published after his death. He wanted to be able to depict the human anatomy in layers on a 5.9 ft. full-size person. Since this was not possible (see end notes), he worked with the artist and engraver Antonio Serantoni (1780 – 1837) to prepare three images of each plate in what is today known as the largest anatomy book ever published. Each page was printed in what is known as “double elephant folio”. To draw each plate, he dissected human bodies with the help of his assistant François (Francesco) Carlo Antommarchi (1780 – 1838).

After his death, with the help of family members and three professors on the Faculty at Pisa University (see end notes), his magnum opus “Icones Anatomiae Universae” (Images of Universal Anatomy”, was released in nine fascicles from 1823 to 1832, comprising 44 hand-colored copperplates and duplicates of each image (44 additional white and black pages) with symbols to identify each anatomical structure. The images depicted life-size layered views of the human body, from muscles to skeleton. These plates, engraved by Serantoni and others, covered the skeleton, viscera, cardiovascular and nervous systems, and more.

Because of the size, and the need to hand-color each of the 44 plates, and the publishing in fascicles, not many of these books were printed. The total number of the prints is unknown. What we do know is that today there are only 16 surviving complete copies of this incredible book, one of which can be seen at the Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions at the University of Cincinnati Medical College.

Following Mascagni's death, a scandal erupted involving his former prosector, Francesco Antommarchi. He took three sets of Mascagni's anatomical plates with him to St. Helena in 1815, where he served as Napoleon's physician. Upon Napoleon's death he stole Napoleon's death mask and passed it as his, attempting to make copies for sale. Defying a court ruling, Antommarchi published an unauthorized edition in Paris between 1823 and 1826. This version used 45 lithographed plates, omitting 24 figures from Mascagni's original and featuring inferior quality compared to the copper engravings. The theft and plagiarism by Antommarchi marred Mascagni’s vision. Only 8 of these books we published, one is lost, 6 are in private hands and the last one is in a library in Colombia.

Dr. Miranda during his presentation at the

XLIII Anatomy Meeting in Chile

Personal note: Research on Paolo Mascagni has been important for me in the search for larger anatomical images. With the help of the University of Cincinnati Daniel Harrison Medical Library, I was able to use scans of Mascagni’s book and digitally join the images to present them as Mascagni intended. These full-size images are now part of my library and the library of my good friend Dr. Randall K. Wolf. The full-size image can also be seen at the Anatomy Learning Lab of the University of Cincinnati.

In 2023 I was invited to lecture on this topic at the Vesalius Triennial AEIMS, Antwerp – Belgium, and the same year at the XLIII Congreso Chileno de Anatomía.

End notes:

1. The “Accademia dei Fisiocritici” was founded in 1691 and is the second oldest scientific society in the world, second only to the “Fellowship of the Royal Society” of London, England, founded in 1660.

2. Andrea Vaccá-Berlinghieri (1772-1826) Professor of Surgery, Giacomo Barzellotti (1768-1839) Professor of Surgery, Giovanni Rosini (1776-1855) Professor of Eloquence. The publisher was Nicolaum Capurro.

Sources

1. “Mascagni. Paolo” Stefano Arieti. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 71 (2008)

2. "Art in science: Giovanni Paolo Mascagni and the art of anatomy". Di Matteo, N; Tarabella, V.; et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 Mar;473(3):783-8.

3. "Books at Iowa: The Great Anatomy of Paolo Mascagni". Eimas, Richard

4. “The Anatomia Universa (1823) of Paolo Mascagni (1755–1815): The memory of a masterpiece in the history of anatomy after two centuries” Orsini, D; Saverino. D; Martini, M. Translational Research in Anatomy Vol 35, 2024, 100285 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2024.100285.

5. “The “prince of anatomists” Paolo Mascagni and the modernity of his approach to teaching through the anatomical tables of his Anatomia universa. A pioneer and innovator in medical education at the end of the 18th century and the creator of unique anatomica” Martini, M; Orsini, D. Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology.

6. “Una autobiografia inedita di Paolo Mascagni relativa specialmente al periodo delle rivoluzioni politiche avvenute in Toscana alla fine del sec. XVIII ed alle persecuzioni subite in tale epoca dal Mascagni stesso” Guerritore, T.G. 1928 Atti della Accademia dei Fisiocritici 10(3) 3-24