Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 440 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

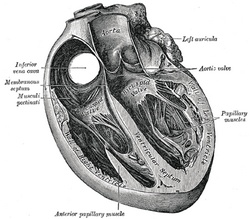

Axial cross-section of the heart

This term is of Latin origin and means "nipple". The plural form of [papilla] is [papillae]. It was first used to describe the renal papillae.

The term [papillary] refers to a structure that resembles a nipple. Some of the uses of the term are:

- Papillary muscle: Muscles of the internal cardiac wall (see image)

- Duodenal papilla: A nipple-like projection in the internal wall of the descending duodenum caused by the hepatopancreatic ampulla (of Vater), also know as the major papilla

- Parotid papilla: An elevation of the buccal mucosa caused by the opening of duct of the parotid salivary gland.

The image shows a section of the heart along its long axis. For a larger view, click on the image

Source:

1. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

2 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

Original image in the public domain, by Henry VanDyke Carter, MD, courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

The medical term [prognosis] is composed by the the Greek prefix [pro-] meaning "forward" and the root term [-gnos-], a derivative of the Greek [γνώση] which means "knowledge".

Prognosis is then "forward knowledge", an statement of outcome of the course of a pathology.

Words suggested by:Sara Mueller

- Details

The word [cava] is of Latin origin, arising from the word [cavus] meaning "hollow". The plural form for cava is cavae.

The term is used in human anatomy to name the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava. Both vena cavae empty into the right atrium of the heart. It is incorrect to refer to both vena cavae as "vena cavas".

The derived root term fom [cavus] is [-cav-] meaning "hollow" or "cavern" and can be found in everyday terms such as "cavern","cavernous", and "excavate" (to hollow out). In human anatomy besides the vena cavae, there are the cavernous sinuses, the cavoatrial junction, etc.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Gabrielle Fallopius

Gabrielle Fallopius (1523 - 1563) also known as Gabrielle Falloppia, was born close to Modena, Italy. He was for some years a priest in the service of the Church, among others as a at Modena's cathedral, but soon turned to medicine. He received his medical degree in 1548 from the University of Ferrara when he was only 25 years old. A professor of human anatomy and surgery at the University of Padua, he was (as Vesalius) critical of the anatomy of Galen. He is known for his accurate description of the uterine tubes, salpinx, or oviducts, which carry his eponym, as the "Fallopian tubes".

His anatomical studies were focused on the anatomy on the head, where he added much to the knowledge of the internal ear and the ethmoid bone.

Less known is the accurate description he made of the inguinal ligament, later named after Francois Poupart. He published only one book during his lifetime, the "Observationes Anatomicae" in 1561. His collected works were published after his death.

Original image in the public domain, courtesy of Images from the History of Medicine

- Details

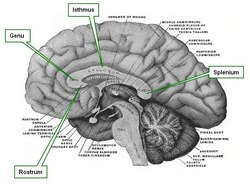

The term [corpus callosum] is Latin. The word [corpus] means "body", while the term [callosum] derives from [callosus] meaning "callous" or a structure with a hard consistency.

The corpus callosum is the largest of the nine interhemispheric commisures of the brain. It is formed by white matter consisting of axons that communicate both cerebral hemispheres. The corpus callosum is formed by several components:

• Rostrum: an anteroinferior region that resembles a bird's beak

• Genu: Latin for "knee", the genu is formed mostly by interfrontal fibers. These fibers form the anterior fornix

• Isthmus:also known as the "body" or "trunk", it is the main portion of the corpus callosum, allowing for interparietal and intertemporal communication

• Splenium: Latin for "bandage" the splenium allows for interhemispheric communication between the parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. The fibers of the splenium form the posterior fornix

The image shown is a median section of the brain. Click on the image for a larger depiction. For a superior view of the corpus callosum click here.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc, Original image courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

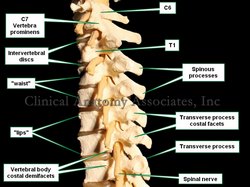

The term [vertebra prominens] is Latin and means the "prominent vertebra". It refers to the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) because of its long spinous process. Because of the anterior lordotic curvature of the cervical spine, their short spinous processes, and the presence of the ligamentum nuchae, the cervical vertebrae are usually not palpable with the exception of the vertebra prominens.

If you slide a finger down the nape of your neck in the midline, the first "bump" that is felt in the spine is the vertebra prominens, the next one down is T1, and so forth.

The vertebra prominens has foramina transversaria as do all cervical vertebrae. The only difference is that the vertebral artery usually is not found in the C7 foramina, opposite of the rest of the cervical vertebrae. The vertebral veins do pass through the foramina transversaria of the vertebra prominens.

Image property of: CAA.Inc. Photographer: David M. Klein