Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 245 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

The root term [-cheil-] derivates from the Greek word [χείλος (keilos]] meaning "lip". There are other medical root terms that also mean lip, but they arise from the Latin words [labellum, labrum, and labra]. There are many medical terms that include the root [-cheil-]:

• Cheilitis: The suffix [-itis] means "inflammation". Inflammation of the lips

• Cheilitis simplex: A very medical way of saying "chapped lips". See accompanying image.

• Cheiloplasty: The suffix [-(o)plasty] means "surgical reshaping". A surgical reshaping or plastic surgery of the lips

• Angular cheilitis: Inflammation of the angle of the mouth, sometimes causing a fissure

• Cheilognathopalatoschisis: This wors combines several roots: [-cheil-], meaning "lip", [-gnath-] meaning "jaw", [-palat-], meaning "palate", while the suffix [-schisis] means "to split". A split or separation of the lip, jaw, and the hard and soft palate.

- Details

The root term [-lapar-] arises from the Greek word [λαπάρα] which means "flank or "loin"". It refers to the lateral region of the abdomen between the costal margin superiorly and the iliac crest inferiorly. In its pure etymological meaning the root term [lapar], as in "laparotomy" or "laparoscopy" should be used to denote a surgical action in only two of the abdominal regions, the right and left lumbar abdominal regions (or flank regions). The suffix [-otomy] originates from the Greek [τέμνω] (tomos) which means "to cut" or "to open".

The first modern use of the term [laparotomy] referring to "an abdominal incision" was in January 1878 by Thomas Bryant, FRCS in his book "A Manual for the Practice of Surgery". This of course caused an upheaval with language purists, as a true laparotomy is a flank incision only. Nonetheless the meaning of the term as suggested by Bryant has been in use since. Today any abdominal incision is a laparotomy.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Insert text here

Giovanni Domenico Santorini (1681 – 1737). Italian anatomist, Santorini was born in 1681 in Venice. The son of an apothecary, Santorini studied medicine at Bologna and Padua, receiving his doctorate in Pisa in 1701. He was appointed Public Professor of Anatomy at the Physicomedical College of Medicine when he was 22 years of age.

Santorini was praised for the clarity of his lectures and his dexterity as an anatomist. He used magnifying glasses to study minute anatomical details, allowing him to clearly describe small structures hitherto unknown. Most of Santorini’s biographical data was written by Michael Girardi (1731 – 1797), one of his students. Girardi published Santorini’s work posthumously in 1775 in the book “Anatomici Summi-Septendecim Tabulae”.

Santorini’s himself wrote “Opuscula medica de structura” (Minute Medical Structures) in 1705. His most important book was “Observationes anatomicae”, published in Venice in 1724. One of the most interesting chapters in this book was “De mulierum partis procreationes datis” (Data on the female procreational structures ), making him a pioneer in the teaching of obstetrics. Santorini was physician to the Spedaletto (Hospital) of Venice, where he taught midwifery.

Santorini died in 1737 because of an infection he acquired during the dissection of a cadaver. At that time the rationale for infection and cadaver embalming were unknown.

With his posthumous publications, Santorini’s name and teachings became popular. Today his name is eponymically tied to several structures in the human body:

• Duct of Santorini: An accessory pancreatic duct that opens into a secondary duodenal papilla in the second portion of the duodenum

• Santorini’s valves: Mucosal folds found in the lumen of the primary duodenal papilla (of Vater) or hepatopancretic ampulla

• Santorini’s muscle: Risorius muscle • Santorini’s cartilages: The laryngeal corniculate cartilages

• Santorini’s veins: A plexus of vesicoprostatic veins found in the retropubic space) of Retzius

• Santorini’s concha: The superior nasal turbinate

Sources:

1. “The Dorsal Venous Complex: Dorsal Venous or Dorsal Vasculature Complex? Santorini’s Plexus revisited” Power NE, et al. BJU Inter (2011) 108: 930-932

2. “Giovanni Domenico Santorini: Santorini’s Duct” Edmonson, JM Gastrointest Endosc (2001) 53:6; 25A

3. "Santorini of the duct of Santorini" Haubrich, WS Gastroenterol 120:4, 805

4. “Wirsung and Santorini: The Men Behind the Ducts” Flati, G; Andren-Sandberg, A. Pancreatology (2002)2:4-11

5. "A Historical Perspective: Infection from Cadaveric Dissection from the 18th to the 20th Centuries" Shoja, MM et al. Clin Anat (2013) 26:154-160

- Details

The [conjoint tendon] (sometimes called the conjoined tendon] is the common tendinous attachment of the internal oblique muscle and the transverse abdminis muscle into the pubic tubercle. Some of these tendinous attachments extend also to the pectineal (Cooper's) ligament, the inguinal ligament, and the superior ramus of the pubic bone. In the classical anatomical description these tendons mix to the point that they cannot be separated one from the other, hence the term [conjoint tendon].

The conjoint tendon is important in open hernia repair, where some surgical techniques require the surgeon to pass a surgical needle and suture through this tendinous structure, to attach or close the gap between the conjoint tendon and the inguinal ligament.

In spite of being described in many anatomy books, a true "conjoint tendon" is only found in about 4% of the cases (varying from 3 to 6%, depending on the author). What is usually found are slightly tendinous discrete structures that attach to the pubic tubercle. Because of this, Skandalakis, et al proposed to change the name to the "conjoined area".

Sources:

1. "Le Tendon Conjoint: Memoire realise dans le cadre du certificat d'anatomie, d'imagerie et de morphogenese" Leroux, H. Universite D' Nantes, 2005

2. "Hernia; Surgical Anatomy and Techniques" Skandalakis, J. et al. 1989 McGraw Hill

3. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

- Details

The word "hyaline" is a derivate of the Greek [υαλώδης] (yalódis) meaning "glassy". It refers to a glassy, transparent substance. Although it is usually associated with hyaline cartilage, this term can be used by itself in daily English.

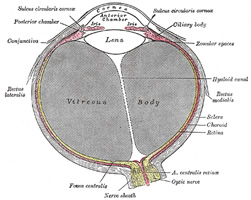

Galen of Pergamon used the term [hyaloid] (glassy, or similar to glass) to refer to the vitreous humor of the eye. As a result of this early anatomical term, today we have the following:

• Hyaloid membrane: also known as the vitreous membrane. It is a collagenous membrane separating the vitreous humor from the rest of the structures of the eye

• Hyaloid artery: a branch of the opthalmic artery which dissapears before birth

• Hyaloid canal: a small membranous canal in the vitrous humor extending between the lens and the optic disc. This can be seen in the accompanying image of a horizontal section of the eye.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

4. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

Image modified from the original by Henry VanDyke Carter, MD. in the book "Grays's Anatomy" by Henry Gray FRS. Public domain

Note: Google Translate includes the symbol (?). Clicking on it will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

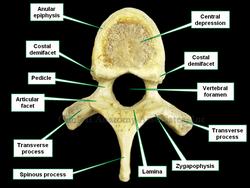

[Anular] means "ring" or "ring-shaped". The word [epiphysis] is composed of the preffix [epi-] meaning "outer" or "above", while [-physis] means "growth". The term [anular epiphysis] means the "outer ring-shaped growth".

The [anular epiphysis], sometimes also called the [anular apophysis], is a bony ring found on the superior and inferior aspect of the vertebrae. This outer ring is formed by thickened cortical bone and leaves a central depression which has a more porous surface. In this central depression the vertebrae present with a thin layer of hyaline cartilage, which forms part of the vertebral endplate.

In a lateral view the presence of the anular epiphysis causes the superior and inferior borders of the vertebral body to protrude. This protrusion is called by some anatomists the "lips" of the vertebrae. To see these "lips" click here.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.Photographer: David M. Klein