Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 255 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

The medical word [avascular] means "without vessels" and refers to structures that do not have vessels providing it with blood supply. Avascular structures, like hyaline cartliage, receive their oxygen and nutrients by diffusion from nearby structures.

The preffix [-a-] means "without", and the root term [-vascul-] means "vessels".

- Details

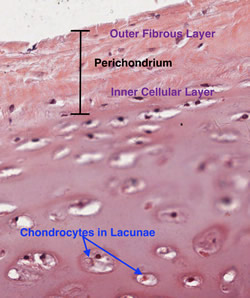

Hyaline cartilage is a type of cartilage characterized by a very homogenous avascular matrix. It is the most common type of cartilage. Hyaline cartilage has a bluish glassy look to it, hence the name.

Within the matrix of hyaline cartilage there are spaces called "lacunae" wich contain chondrocytes. These produce and maintain the extracellular matrix. Hyaline cartilage is found covering articular surfaces allowing for effortless sliding of the articular surfaces one against the other. Hyaline cartilage is avascular.

The accompanying image is a histology slide of hyaline cartilage. For more information on hyaline cartilage, read the article "The Importance of Hyaline Cartilage"by Dr. Stephen Gallik.

The word "hyaline" is a derivate of the Greek [υαλώδης] (yalódis) meaning "glassy".

Thanks to Dr. Stephen Gallik for the mage and links. For more information on mammalian hystology, you can visit Dr. Gallik's website here.

Note: Google Translate includes the symbol (?). Clicking on it will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

This term has two roots terms and a suffix. [-sacr-] means "sacred" , but in this case refers to the sacral bone or sacrum. [-colp-] means "vagina", and the suffix [-opexy] means "fixation", "surgical fixation", or "suspension". As always, the [-o-] between the initial two root terms means "and". Following the rules to combine root terms, the word [sacrocolpopexy] means "fixation of the sacrum and vagina". The term "sacrocolposuspension" is synonymous with "sacrocolpopexy"

The fixation or suspension can be attained by the use of sutures, surgical staples, bone tacks, mesh, etc. or a combination of these devices. A sacrocolpopexy can be needed in the case of a weakened or damaged pelvic diaphragm that can lead to urinary incontinency and recurrent urinary infections, among other problems.

• For a procedural video of sacrocolpopexy click here. WARNING: The video is age-restricted

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Mondino de Luzzi (ca.1270 – 1326). Italian anatomist, born Raimondo de Luzzi in the city of Bologna circa 1270. He was also known as Mondino, Remondino, or Mundinus de Leutiis, de Lentiis, de Lucci, and other variations of his name. His father Nerino Franzoli was an apothecary, and Mondino also started working as such.

In 1290 he enrolled in the Medical School at the University of Bologna obtaining his medical degree circa 1290. Mondino stayed at the university, where he continued to teach until his death in 1326.

His major publication is “Anothomia Corporis Humani”, written circa 1316 and found only in manuscript form. It was finally printed in movable type in 1478, making it easily available to the public. While some authors like Singer, 1925 contend that this is his only publication, others discuss the possibility that Mondino de’ Luzzi wrote other books that have been adjudicated to other authors as at the time the name “Mondino” was very common.

“Anothomia Corporis Humani” is the first anatomical book based on actual dissections, and the book was organized almost as a dissection manual, explaining dissection techniques to visualize specific structures. Initially this book had no illustrations, but some were added in later publications.

With over 40 editions, the last one in 1668, this book was used for almost 250 years. Mondino restarted human dissections in medical schools almost 1,500 years the medical school of Alexandria, leading many to call Mondino the “restorer of anatomy”.

It is said that Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) used one of Mondino’s books as a dissection manual to guide his own. Because Mondino followed Galen’s dictums and teachings, he was harshly criticized for his errors by Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564).

Although it is not clear if Mondino himself performed the actual dissections (he says he did), it is clear that he directed them. We know of two of his assistants: Otto Agenio Lustrolanus and Alessandra Giliani, the first woman prosector and anatomist. When Mondino died the same year as Alessandra Giliani, the expectation was that his assistant would continue the work of the master. Sadly Otto Agenio Lustrolanus died before he was 30 years old.

In the introduction to “Anothomia” Mondino says: "A work upon any science or art-as saith Galen-is issued for three reasons: First, that one may satisfy his friends. Second, that he may exercise his best mental powers. Third, that he may be saved from the oblivion incident to old age. Therefore, moved by these three causes, I have proposed to my pupils to compose a certain work on Medicine.”

"And because a knowledge of the parts to be subjected to medicine (which is the human body, and the names of its various divisions) is a part of medical science, as saith Averrhoes in his first chapter, in the section on the definition of medicine, for this reason among others I have set out to lay before you the knowledge of the parts of the human body which is derived from anatomy, not attempting to use a lofty style, but the rather that which is suitable to a manual procedure."

Sources:

1. “Mondino de' Luzzi's commentary on the Canones Generales of Mesue the Younger” Welborn, MC. Isis , 22: 1 (1934) , 8-11

2. “Medieval neuroanatomy: the text of Mondino dei Luzzi and the plates of Guido da Vigevano” Orly R. J Hist Neurosci. 1997 6 (2):113-123

3. “Mondino de Luzzi (1270-1326) Restaurador de la Disecci?n Anat?mica” Rever?n, RR. Informe Medico 2007; 9 (12):589-592

4. “The history and illustration of anatomy in the Middle Ages” Gurunluoglu, R, et al. J Med Biogr 2013 21: 219 – 229

5. “The Mondino Myth” Pilcher, LS. 1906

Original image courtesy of NLM

- Details

Cartilage is a type of avascular tissue with a highly specialized extracellular matrix that contains chondrocytes. The condrocytes produce and maintain the extracellular matrix. The root term meaning [cartilage] is [-chondr-], which originatesfrom the Greek [χόνδρος] or [chondros] meaning "cartilage" or "gristle". The Latin equivalent is [cartilago] giving us the synonymous root term [-cartilag-], from which [cartilage] arises.

The matrix contains large amounts of glicosaminoglycans, which allows for easy diffusion of substances from surrounding structures and blood vessels. Being avascular, cartilage does not have its own blood supply. The extracellular matrix also has large quantities of hyaluronic acid, which allows cartilage a weight-bearing capacity. This is why cartilage is particularly useful in bony joints and covering articular surfaces.

There are three types of cartilage present in the human body:

• Elastic cartilage: This type of cartilage is characterized by elastic fibers, usually in layers or lamellae

• Fibrocartilage: This type of cartilage is characterized by large bundles of collagen, making it look and feel fibrous

• Hyaline cartilage: This type of cartilage is characterized by an homogenous amorphous matrix

Thanks to Dr. Stephen Gallik for the mage and links. For more information on mammalian hystology, you can visit Dr. Gallik's website here.