Theo Dirix

Note: The following article was recently published in Dutch by my good friend Theo Dirix. Theo is one of our "Vesaliana" contributors, and he has written or has been part of several of the articles in this website. Theo was kind enough to provide a translation of his publication for this blog. There are footnotes in the original publication and I have added them to the end of this article. Dr. Miranda

Christie’s in New York recently sealed the deal of an exceptional copy of the Fabrica, the masterpiece by Andreas Vesalius. The sound resonated widely: buyers were the alma mater of the doctor, the KULeuven (University of Louvain, Belgium), and the Flemish government.

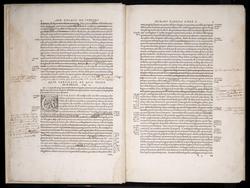

Earlier, a copy of Vesalius’s 1538 adaptation of a teacher’s manual, with his own notes, had already gone under the hammer. This copy of the second edition of the Fabrica from 1555, also richly annotated by the author, was not allowed to escape.

Vesalius enthusiasts eagerly anticipate seeing this historical wonder with their own eyes, following the promised digitization by the KULeuven and its exhibition in their ‘experience center’.

Non-medical or non-Latinist individuals may also find Vesalius captivating. The allure of such a well-traveled, exceptionally driven, and art-loving man is infectious and timeless. The Inquisition had no control over him, and his free-spirited mind and interactions with those of differing beliefs, such as Protestants or Jews, continues to inspire today.

At the end of the First Book of the Fabrica, there is a list of names for the bones of the skeleton as Vesalius knew them: first as he himself preferred to use them, then in Greek and in the Latin of others, and finally in Hebrew. In a certain way, the latter is also the Arabic translation, so he says, as they are “almost all taken from the Hebrew translation of Avicenna by my good Jewish friend and eminent physician Lazarus de Frigeis (with whom I usually study Avicenna).” 1

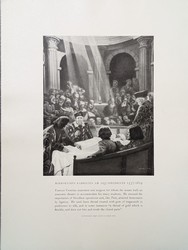

The opening print of the Fabrica may even feature an image of his friend. After all, Vesalius had one of his public dissections illustrated. 2

"A colorful crowd, rows deep, stands, hangs, and drums around the table on which a corpse is being dissected. Three quarters of almost two hundred guests are students, with about fifty doctors and other notables also in attendance."

That is how the German student Baldasar Heseler described in his diary a public dissection in Bologna, conducted by the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius.

Among the attendees were likely curious individuals who also frequented public executions or animal fights. Dissections were not serene practical lessons like today. Sometimes several dissections followed each other, often chaotic and in a festive atmosphere during the carnival period: today a hanged man, tomorrow a prostitute, in between a dog.

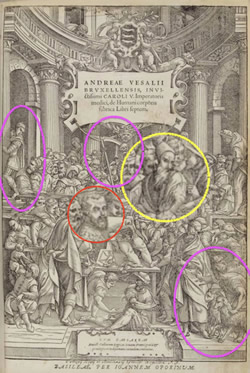

The image Vesalius chose for his first version of the Fabrica in 1543 is more symbolic in nature. Various authors see allegories in the ninety characters, as well as historical and contemporary prominent figures and acquaintances. 3

A striking figure who is central yet isolated is a man with a long beard, red in some colored versions, wearing a truncated conical headdress such as a tarboosh or fez. He turns towards his neighbor who whispers or shouts something to him. Or is he responding to the scene unfolding beneath him with the dismissive gesture of his left hand? With understanding or disgust?

Like other guests, he wears a heavy cloak; dissections were preferably performed during the cold winter months. It may be far-fetched, but don’t those stripes on his cloak remind us of the threads of a Jewish prayer shawl? Is this “his good Jewish friend and leading physician Lazarus de Frigeis”?

In the opening print of the second version from 1555, the stripes or threads are less clear. The sharp gaze is also blurred. And isn’t that beard shorter? Things have indeed changed in twelve years.

For example, the originally naked spectator on the balcony now wears a suit. The dog, bottom right, has a goat or goat next to him: is that perhaps the devil? The pennant of the all-dominating skeleton in the center becomes a scythe in the hands of Death.

Many find the later image less appealing than the original and speculate as to the reasons: Was it created by a different and perhaps less talented artist? Was the initial woodcut set aside because it had already been extensively used? Do the alterations suggest censorship or self-censorship, perhaps with an eye towards the advancing Inquisition?

Vesalius also made numerous changes to the text in the second edition. It remains a mystery how he communicated these changes to his Basel printer, Oporinus. This curiosity extends to his annotations and the third edition he had in mind. For instance, in the second edition, he omitted all references to his friends, retaining only the mention of Lazarus de Frigeis. However, the descriptors ‘Jewish’ and ‘leading physician’ were removed. Lazarus is still described as “his good friend.” Why did the reference to Judaism have to vanish?

One explanation posits that the descriptor ‘Jew’ had become redundant. Following the perspective of a researcher who identifies Lazarus de Frigeis as Lazzaro Freschi, the son of Rabbi Raffaele Fritschke, it is thought that Lazarus converted to Christianity in 1549, assuming the name Giovanni Battista Freschi Olivi. 4

Another explanation suggests that it may have been safer at the time to avoid allusions to Jewish beliefs or conversions. According to the same source, Lazzaro Freschi and his mother moved, or were compelled to move, to the Venice ghetto in 1547.

The word ‘getto’ is Italy’s ‘contribution’ to anti-Semitism, akin to later terms such as ‘pogrom’ from Russian, ‘Endlösung’ from German, and the slogan in English today commonly heard on European streets: “From the River to the Sea”.

Vesalius, however, continued to refer to Lazarus de Frigeis as his good friend. Not only was the anatomist well-traveled, passionate about his work, and an admirer of art, he was also loyal, open-minded, and, above all, courageous.

Theo Dirix

With gratitude to Omer Steeno, Maurits Biesbrouck, and Theodoor Goddeeris

Footnotes:

1. based upon: Maurits Biesbrouck. Nederlandse vertaling van het eerste boek van Andreas Vesalius’ Fabrica 1543, handelend over het Menselijk Skelet. P. 394.

2. with differences in the frontispieces of the Fabrica’s of 1543 and 1555: https://exhibitions.lib.cam.ac.uk/vesalius/

artifacts/coloured-frontispiece-1543/, and https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/vesalius500/fabrica/a-tale-of-two-title-pages

3. for example: C.D. O’Malley. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los

Angeles, 1964, p. 140.

4. Toaff, Ariel. Pasque di sangue, Ebrei d’Europa e omicidi rituali, Societa editrice il Mulino, Bologna, 2007, p. 197 - 198