Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1500 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Jean-Annet Bogros (1786 - 1825) French physician, surgeon and anatomist. He was born in Bogros, a village in the mountains d’Auvergne, France.His family wanted him to become a priest, but his inclination towards medicine took him to an apprenticeship in the Hôtel-Dieu de Clermont, a hospital under the tutelage of Drs. Fleury, Lavort, and Bertrand. He continued his studies in Paris where he excelled at anatomy. He soon became an intern in Paris Hospitals, and in 1817 he became an assistant at the Faculty of Medicine. He was praised for his anatomical and surgical skills.

In August 29, 1823 he submitted his thesis for his Doctorate in Medicine “Essai Sur L’Anatomie Chirurgicale de la Region Iliaque: Et Description D’un Nouveau Procédure Pour Faire La Ligature Arteres Epigastrique Et Iliaque Externe”. His thesis challenged and improved the technique of ligation of the epigastric and iliac vessels proposed by Abernathy and Astley Cooper. His teaching rivaled the Astley Cooper technique, with an emphasis on hemostasis that was well recognized at the time.

Today his name is eponymically tied to the subinguinal space of Bogros, a triangular area posterior to the superior pubic ramus, lateral to the space of Retzius. This area is bound anteriorly by the deep preperitoneal fascia, and posteriorly by the peritoneum. The medial boundary of this space is either the lateral wall of the urinary bladder, or a sagittal plane passing at the origin of the inferior (deep) epigastric vessels. The superior boundary is the inguinal ligament, while the inferior and lateral boundaries are not described.

Bogros died in 1825 when he was 39 years of age. His cause of death in unknown, but many postulate tuberculosis.

Unfortunately, he was a good and simple man and was described as being meek and soft-spoken. Because of this, he only left one posthumous publication (1827) “Mémoire sur la Structure des Nerfs” where he explains a novel system to inject and identify nerves. This publication, in French, can be read and downloaded here.

Some biographical articles wrongly show his name as Jean-Antoine Bogros, others change the name to Annet Jean Bogros. Both are not correct. In our research we could not find a portrait of Bogros, so we used the cover or his posthumous memoir on the structure of the nerves.

Sources:

1. “Totally Extraperitoneal Herniorrhaphy (TEP): Lessons Learned from Anatomical Observations” Xue-Lu Zhou; Jian-Hua Luo; Hai Huang, et al. Minimally Invasive Surgery 2021(1):5524986

2. "Crucial steps in the evolution of the preperitoneal approaches to the groin: An historical review" R.C. Read Hernia 2010. 15(1):1-5

3. "Retzius and Bogros Spaces: A Prospective Laparoscopic Study and Current Perspectives" Ansari, MM Annals of International Medical and Dental Research, 2017 Vol (3), Issue (5) 25-31

4. " The Preperitoneal Space in Hernia Repair" Lorenz, A et al. Front Surg (2022) Visceral Surgery Vol 9

5. "Essai Sur L’Anatomie Chirurgicale de la Region Iliaque:: Et Description D’un Nouveau Procede: Pour Faire La Ligature Arteres Epigastrique Et Iliaque Externe” J.A. Bogros Imprimerie de E. Duverger. 1827 Paris

- Details

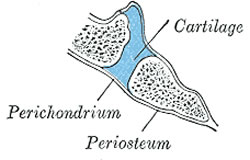

Sagittal section through the clivus of the skull

demonstrating the location of the sphenooccipital

synchondrosis in an infant.

A synchondrosis (plural: synchondroses) is a type of cartilaginous joint characterized by a plate of hyaline cartilage that joins two bones. It is also known as a “primary cartilaginous joint”.

Since a synchondrosis practically has no movement, it is classified as a synarthrosis (plural: synarthroses) an immovable joint. All synchondroses are synarthrotic.

Because of the way bones mature, there are many skeletal synchondroses present while the individual matures, an important group of synchondroses are those of growth plates in long bones at the junction of the epiphysis and the body or shaft of the bone. These disappear when the individual reaches full skeletal maturity.

In the older individual there are a few synchondroses, one of them is found at the joint between the first rib and the sternum, others are found at the costochondral joint, the joint between the ribs and the costal cartilage.

There may be some synchondroses found in areas of skeletal anomalies, like the os acromiale, and tarsal coalitions.

Etymology: The word “synchondrosis” derives from the following medical terminology components: The Greek prefix [σύν] (sýn) meaning “along, with, or plus”, the Greek root term [χόνδρος] from [χόνδρος αρθρώσεων] (chóndros arthróseon), and the suffix [-osis], also Greek, meaning “condition”, “state of” or “many”. The term “synchondrosis” can be loosely interpreted as a “condition with cartilage”.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

4. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

Image modified from the original by Henry VanDyke Carter, MD. in the book "Grays's Anatomy" by Henry Gray FRS. Public domain

- Details

UPDATED: One year ago, on Monday January 2nd 2023, Damar Hamlin suffered a cardiac arrest as a consequence of a tackle that impacted his chest. The football player had suffered a Commotio Cordis, a rare but known athletic cardiac injury that was reversed by the medical support teams present at the Cincinnati Football Stadium.

One year later, the University of Cincinnati has published a press release entitled "The Damar Hamlin Effect: Revolutionizing CPR and AED Training Nationwide". Because of this accident, the awareness for training in CardioPulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and the need and availability of Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) has increased. His foundation has to-date raised over 9 million dollars!

Following is the original (and updated) post:

I have received several questions regarding this term and its meaning, because of the cardiac arrest suffered on the field by the Buffalo Bills defensive player Damar Hamlin while playing the Cincinnati Bengals on January 2nd, 2023.

For those who were watching the game, close to the end of the first quarter Hamlin blocked another player in what looked like a normal and standard play. Immediately after, Damar Hamlin stood up and immediately collapsed. The video can be seen here. The player was treated on the field and later reports indicated that he had suffered a cardiac arrest and was treated with CPR (manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation), the use of an AED (Automated External Defibrillator) and oxygen. The player was intubated and was considered to be in critical, but stable condition.

The consensus is that Damar Hamlin suffered a ventricular arrhythmia, which allowed the heart to beat erratically, but not be able to pump blood, which is why he had to be defibrillated using the AED.

The cause for this is an uncommon (30 cases per year in the US) but known situation known as Commotio Cordis, a ventricular dysrhythmia caused by a sudden hit to the sternum in a particular location*. It has been seen in baseball and softball players where the pitcher is hit in the sternum by a fast ball coning from first base. Also seen in lacrosse players. In most cases this happens in younger individuals where the four sternabrae that form the body of the sternum have not yet completely ossified, making the sternum and lower costal cartilages quite flexible, being able to “bend in” when hit directly and compress the heart.

As some of you may know, I am a 7th Degree Black Belt in Goju-Ryu Karate. This type of punch to the sternum is one of the many techniques used in advanced Martial Arts. In most cases this punch will slow down an opponent, but it does not cause Commotio Cordis. It is a technique that should only be practiced under very close supervision. In fact, this technique was thought to be legend and was called “the touch of death” in China.

Commotio Cordis at a karate tournament

An example of Commotio Cordis caused by a Karate punch can be see in the following YouTube video. The image in this article shows the instant the chest strike happens at 6 seconds in the video. Look at the hand of the practitioner on the right and the devastating consequence that follows. Please note the similarity of the situation in this video and what happened to Damar Hamlin. There is a lapse of time between the Commotio Cordis cardiac arrest where the athlete gets up or walks followed fainting and unconsciousness. What is distressing is that the young martial artist who suffered this devastating injury died at the tournament. The judges were not aware of the situation, no one felt his pulse, or started life-saving CPR. Because of the content this video is age-restricted and you may have to sign in to view it.

The words are Latin. Commotio means “agitation or commotion”. Cordis means heart. The conditions to cause Commotio Cordis need to be exact, as the heart needs to be in ventricular repolarization, when the heart ventricles are starting to refill with blood. The "window" for a sternal hit to cause Commotio Cordis is very small.

Please, if you do not know how to provide CPR, take a full CPR course or at least attend a short 10 minute training like the one provided by University of Cincinnati Health in their "Take 10 Cincinnati" program.

For additional information please visit StatPearls at https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/19761

- Details

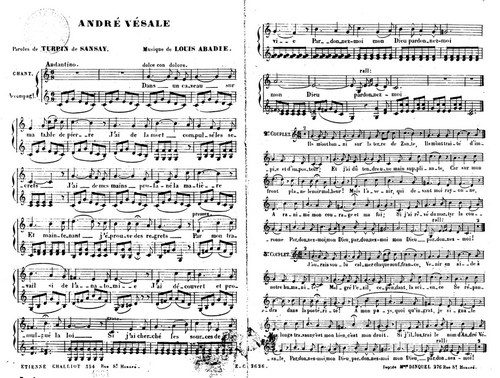

How many scientists, physicians, or anatomists have musical pieces written for them? I was so surprised when I found out that there is a musical score entitled “André Vésale” written by Louis-Jean Abadie and published in 1861 in Paris, France. I felt the obligation to research this topic.

There are many people that follow the life and works of Andreas Vesalius, a 16th century anatomist who started the modern scientific approach to human anatomy and medicine. I count myself in this group that includes artists, historians, poets, painters,musicians, medical illustrators, physicians, surgeons, antique collectors, anatomists, etc.

In June 2023, I had the honor of being invited by the University of Antwerp in Belgium to speak at the 2023 Vesalius Triennial Meeting. It was here that I discovered this musical surprise!

One of the events of this meeting was an afternoon concert entitled “Vesalian landscapes in music, poetry, and photographs” by pianist Elke Robersscheuten, and my friend Theo Dirix, who read the poetry. This was accompanied by slides of Vesalian works, and images of the city of Brussels and the island of Zakynthos, Greece. One of the pieces performed by Elke Robersscheuten was “André Vésale”. You can see Elke perform this piece in a video at the end of this article.

With the help of Theo, I started the process of unraveling the story of this musical piece:

The author

Abadie, Louis-Jean (c1814-1858). Louis Abadie was a baritone singer. He started performing in the French provinces as member of an opera troupe. In 1842 he settled in Paris where he wrote numerous chansons and romances which were very popular at the Paris salons at the time. He had success as singer and voice teacher in Paris and in 1848 he released records of his songs, which were well received. I have not been able to find copies of these records.

He went back to traveling and singing, with little success and decided to move to Bordeaux, and then back to Paris where he was unsuccessful trying to find a locale that would present his work to the public. He lived in poverty and in early December 1958 he had a stroke and died at 45 years old, leaving a wife and three children. As a side note to his life, many of his works were dedicated or mentioned by name a woman named Jeanne. His wife's name was Marie Jeanne Toussaint.

Seven years after his death, on May 2, 1867, Les Danseurs de Corde.(The Rope Dancers) , an operetta (comedic opera) in two acts for which he had written the music, was performed at the Théâtre des Folies-Saint-Germain.

The lyrics

The poignant lyrics to this work were written by Louis-Adolphe Turpin de Sansay (1832 – 1891) a prolific French dramatic author, chansonnier, and songwriter. He collaborated with musicians with lyrics for their work. The lyrics for “André Vésale” were written in 1860 and published the following year.

The works of Turpin de Sansay were presented in elite places line the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, the Théâtre Beaumarchais, and the Théâtre-Lyrique.

The lyrics for “André Vésale” are based on Vesalius being deported to the Greek island of Zakynthos (known then as Zanthe). We now know this is a legend and not true. Following is the French original and a free translation of this work:

"André Vésale" (French)

Dans un caveau sur ma table de pierre

J'ai de la mort compulsé les secrets.

J'ai de mes mains profané la matière,

Et maintenant j'éprouve des regrets.

Par mon travail si de l'anatomie

J'ai découvert et promulgué la loi:

Si j'ai cherché les sources de la vie,

Pardonnez-moi, mon Dieu, pardonnez-moi!

Ils m'ont banni sur la terre de Zante,

Ils m'ont traité d'impie et d'imposteur;

Et j'ai dû tendre une main suppliante,

Car sur mon front plane le noir malheur!

Mais l'avenir, qui devant moi rayonne,

A ranimé mon courage et ma foi;

Si j'ai rêvé du martyr la couronne,

Pardonnez-moi, mon Dieu, pardonnez-moi!

J'aurais voulu calmer chaque souffrance,

Venir en aide à notre humanité,

Malgré l'exil, cependant, la science

Se répandra dans la postérité!

A mon pays, quoi qu'ingrat, je signale

Mes longs travaux, c'est mon bien, c'est mon droit.

Si j'illustrai le nom d'André Vésale,

Pardonnez-moi, mon Dieu, pardonnez-moi!

"Andreas Vesalius" (English)

In a cellar, on my stone table

I have extracted the secrets of death.

I have desecrated matter with my hands,

And now I feel regret.

By my work of anatomy

I discovered and promulgated the law:

If I sought the sources of life,

Forgive me, my God, forgive me!

They banished me to the land of Zakynthos,

They called me impious and impostor.

And I had to hold out a pleading hand,

For on my forehead hovers black misfortune!

But the future, which shines before me,

Revived my courage and my faith.

If I dreamed of the martyr's crown,

Forgive me, my God, forgive me!

I would have liked to calm each suffering,

Come to the aid of humanity,

Despite the exile, however, science

Will spread to posterity!

To my country, although ungrateful, I point out (that)

My vast work is my property, it is my right.

If I inscribe the name of Andreas Vesalius,

Forgive me, my God, forgive me!

The publisher

Étienne Challiot (1837 – 1866) had his office located at 352-354 Rue St Honoré, in Paris, very close to Place Vendôme, Paris. He published books and music sheets. Some of his publications can be found online.

The printer

Almost nothing is known about the printer of this work. A female printmaker, Madame Dinquel, had her printer shop at 276 Rue Sain Honoré, in Paris, very close to the publisher Étienne Challiot. Today, Sapporo, a Japanese restaurant sits at this address.

The musical piece

Following is a video of pianist Elke Robersscheuten performing "André Vésale" by Luis Abadie.

The original score can be downloaded here. Thanks to IMLSP for preserving this music for posterity. You can click on the image for a larger depiction.

André Vésale sheet music by Luis Abadie. Public Domain

Sources:

1. Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique, Volume 1François-Joseph Fétis Libraire de Firmin-Didot, 1878 Paris

2. Obituary: Courrier de la librairie: journal de la propriété littéraire et artistique pour la France et pour l'étranger. 1858,7/12

3. Necrologie; B. JOUVIN. Théatres (French). Paris: Figaro, 09/12/1858. Article nécrologique dans Le Figaro (Lire en ligne sur Gallica)

4. Obituary: Courrier de la librairie: journal de la propriété littéraire et artistique pour la France et pour l'étranger. 1858,7/12

5. Frédéric Caille, La figure du sauveteur : Naissance du citoyen secoureur en France, 1780-1914, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2006, p. 222-224 6.

- Details

The term “lesser curvature” refers to the shorter, curved, and concave right-sided border of the stomach. The lesser curvature extends between the esophagogastric junction superiorly and the pylorus inferiorly.

Although generally curved, the lesser curvature presents with a sharp angulation called the incisura angularis or the angular notch.

The lesser curvature is connected to the liver by a double-layered fold of peritoneum called the lesser omentum. The lesser omentum is composed of two regions:

1. The gastrohepatic ligament, the larger component, found between the lesser curvature and the liver. It includes the pylorus.

2. The gastroduodenal ligament, the smaller component, found between the first portion of the duodenum (superior portion, duodenal ampulla) and the liver. The common bile duct is found between the layers of the omentum.

The image shows the lesser curvature with an animated dashed line. The blue arrow points to the incisura angularis.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Original pastel image by Dr. E. Miranda

- Details

The term "incisura" is Latin, derived from the verb [incidere]* meaning "to cut" or [incisura]” meaning a "notch" or indentation in a structure, suggesting a distinctive incision, or cut. The second component, "angularis," is also Latin, derived from "angulus," which translates to "angle." The term "incisura angularis" can be translated as the "angular notch", a term that is also use for this gastric anatomical landmark.

The incisura angularis is a notch located along the lesser curvature of the stomach. Externally, it marks the transition between the body (corpus) and antrum of the stomach, an abdominal viscus. It is related to the gastrohepatic portion of the lesser omentum superolaterally. It should be mentioned that the lesser curvature vascular arcade runs within the lesser omentum, closely related to the gastric lesser curvature.

Found approximately midway between the esophagogastric junction and the pylorus, this external anatomical feature is easily identifiable internally during gastric endoscopy.

Structurally, the incisura angularis is formed by a fold of mucous membrane on the inner surface of the stomach, creating a small recess along the lesser curvature.

The stomach, although it has the same layers as the rest of the GI tract, presents an extra muscular layer in the area of the lesser curvature, which renders this area less distensible forming a muscular channel called the magenstrasse.

The mucosa layer is the deepest of the stomach layer. Within it, three areas of gastric mucosa are usually described: pyloric, transitional, and fundic. The incisura angularis corresponds mostly to the transitional zone. When there are mucosal changes that shown an invasion of another type of mucosa, it can mean preneoplastic changes. For this reason, the incisura angularis is an area that, when biopsied, can show early cancerous changes, as well as muscular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia.

Preservation of the anatomy of the incisura angularis is critical during a sleeve gastrectomy, the most common bariatric procedure worldwide. The objective of a sleeve gastrectomy is to reduce the size of the stomach by placing a curved staple line along the left border of the magenstrasse, a lesser known gastric anatomy term.

Because of the location of the incisura angularis, improper placement of a straight gastric stapler could cause stenosis or stricture at this level. Another potential postoperative problem in this procedure is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) where some authors have proposed an omentopexy as a way to modify the angle of the incisura angularis.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

3 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

4. “The Rarely Sampled Incisura Angularis Is Useful for the Detection of Gastric Preneoplastic Lesions” Singhal, A. , Saboorian, H. , Turner, K. , Rugge, M. & Genta, R. (2023). The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 118 (10S), S1407-S1407.

5. “Incisura angularis belongs to fundic or transitional gland regions in Helicobacter pylori-naive normal stomach: Sub-analysis of the prospective multi-center study” Nakajima, S at al Digestive Endoscopy 2021; 33: 125–132

6. “Increasing the angle at the incisura angularis using omentopexy reduces/prevents GERD symptoms five years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy?” Presidential Grand Rounds. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, Volume 18, Issue 8, Supplement, 2022

7. “Gastric POEM to treat incisura angularis torsion after sleeve gastrectomy” Baptista, A; Davila, M; Guzman, M. Endoscopy 2019; 51(04)

8. “Obstruction after Sleeve Gastrectomy, Prevalence, and Interventions: a Cohort Study of 9,726 Patients with Data from the SOReg” Sillen, L; Andersson, E, Edholm, D. OBES SURG 31, 4701–4707 (2021)

Note: Google Translate includes the symbol (?). Clicking on it will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.