Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 346 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

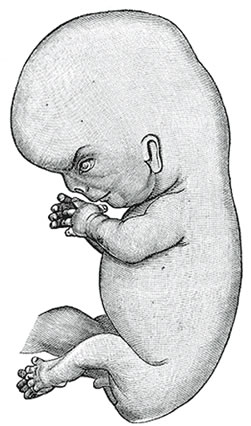

Lateral view - Human embryo about

eight and a half weeks old

(UPDATED) The term [ventral] arises from the Latin word [venter] and the root term [ventr-] meaning "belly" or "sac". The adjective [ventral] means "towards the front" , or "towards the belly side of the body". The term ventral therefore means "abdomen".

Many use the term [ventral] synonymously with "anterior"; although this is technically correct, the proper term to use when referring to the patient in the anatomical position should be "anterior". In embryology, since the embryo is curved, most of the anterior aspect of the embryo looks towards the abdomen, ergo ventral.

A ventral hernia is any herniation that occurs in the anterior aspect of the abdomen, including Spigelian hernias, omphaloceles, etc.

Other terms that arise from the same root term are [ventricle], meaning "little belly", or "little sac", and [ventricular], meaning "pertaining to a ventricle".

Note: A comment from my friend Dr. Elizabeth Murray:

"My understanding of "anterior" means "in the direction of movement" for any given organism (and "posterior" means opposite the direction of movement for an organism). Thus, ventral does not ever change for any creature (vertebrate or even invertebrate), as it refers to a body part/surface. But when considering two-legged and four-legged (or finned) creatures, you see the differences: Ventral = anterior in us, but in a dog or fish ventral = inferior.

Ventral/dorsal refer to belly/back in any organism, and cranial/caudal refer to head-end and tail-end in any organism -- those four terms refer to body parts. However, anterior/posterior refer to the way an organism moves in space, and superior/inferior refer to an organism's relationship to the earth/pull of gravity."

An interesting side note: The word [ventriloquist] arises from the root term [-ventri-] from the Latin [venter] and the suffix [-loquist], from the Latin [loquos] and [locutus], meaning "to speak", or "someone who speaks". The term [ventriloquist] means then "someone who speaks from the abdomen (or stomach)". We now know that this is not so, but that is what most people think a ventriloquist does!

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD., courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

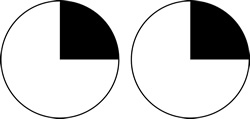

Right homonymous superior quadrantanopia

[Quadrant]-[an-[opia ] The root “quadrant” is based on the Latin "Quadri" meaning "four" and “Quarto”, meaning one fourth. The suffix anopia is composite: “an” meaning “without or absence of”; and opia (or “opsia”) relate to vision, based on the Greek word “οπτασία” (optasía) meaning “sight”. Literally, the term quadrantanopia (or quadrantanopsia) means “absence of sight in a quadrant”.

It can be associated with a lesion of an optic radiation of the internal capsule. While quadrantanopia can be caused by lesions in the temporal and parietal lobes of the brain, it is most commonly associated with lesions in the occipital lobe.

What is interesting are the terms “homonymous” and “heteronymous” used to describe variants of quadrantanopia. Each eye has four quadrants and two visual fields, right and left. A homonymous quadrantanopia means that the patient has lost the vision of a quadrant in the same field in each eye (right-right or left-left), heteronymous means that the patient has lost the vision of a quadrant in the opposite field of each eye (right-left or left-right).

The fact is that the term homonymous means “same name” not same side, and the word heteronymous means “different name”, from the Greek “όνομα” “nym” meaning name. For further confirmation, try finding the meaning of synonym, antonym, acronym, patronymic, etc.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

3. "Dorlands's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" 26th Ed. W.B. Saunders 1994

Note: Google Translate includes an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word

Image courtesy of Mudsk, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 2083

I had the honor of being invited to participate in the 53rd Annual Chilean Meeting of Anatomy (XLIII Congreso Chileno de Anatomía) which was held in conjunction with the 1st Latin American Congress of Clinical Morphology (Primer Congreso Latinoamericano de Morfología Clínica). Along with these meetings were two symposia: The First Joint Symposium of Chilean/Korean Anatomists and the First Joint Chilean - IFAA-FIPAE Symposium (International Federation of Associations of Anatomists - Federative International Program for Anatomy Education).

Universidad de Los Andes, Chile

This meeting was held on November 11- 14, 2023 and was hosted by the University of Los Andes (Universidad de Los Andes), a Chilean institution of private higher education that offers careers and postgraduate programs in different areas of knowledge including Education, Engineering, Nursing, Obstetrics, Medicine, Psychology, Law. etc. Their campus is located on the slopes of the beautiful Andes mountains overlooking the city of Santiago, Chile.

The image shows the Main Library of the University, where the meeting was held.

On November 9 and 10, the days leading to the meeting, there were six Postgraduate Courses, from anatomy to radiology and surgical reconstruction. There were two that I would like to highlight. The first one was a workshop "Mastering Anatomical Radiology with IMAIOS", where one of the instructors was my good friend Dr. Cristian Uribe, who was one of the Meeting organizers. Dr. Uribe is one of the contributors to Medical Terminology Daily.

The second one was a "Workshop on Art & Science: A Theoretical-Practical Course on Anatomical Illustration". This course was directed by my good friend, Dr. Carlos Machado, world-renown medical illustrator, physician, and anatomist, editor of Netter's Atlas of Anatomy. Along with him two professors, Drs. Daniel Casanova and Valentina Cerda.

The Meeting was officially opened by Dr. Juan Carlos Lopez, Director of the Morphology Department of the Los Andes University. This was followed by a presentation on "The Role of the Placenta on the Modulation of Human Potential" by Dr. Sebastian Illanes. On the picture, from left to right, Dr. Jens Wasche (Germany), Dra. Valentina Cerda (Chile), Dr. Carlos Machado (Brazil/USA), me (Chile/USA), and Dr. Andres Riveros Valdes (Chile), a good friend and anatomist. Dr. Riveros is the President of the LatinAmerican Meeting on Clinical Morphology.

There were so many great presentations in this meeting! I think the attendees will agree with me that the conference by Dr. Carlos Machado on "The Art of Learning and Teaching Anatomy with Art" was one of the highlights of the Meeting. In his presentation Dr. Machado shared some of his early drawings and his career in Medicine and Medical Illustration, how he has used art to show patient pathology, and most important, the work and dedication that is required when developing a single image that will later become part of the Anatomy Atlases with which he collaborates.

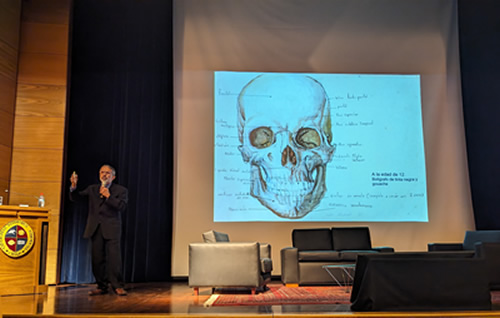

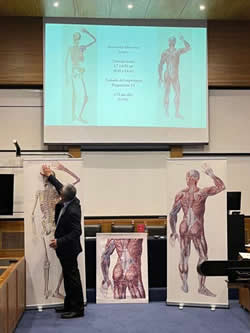

The image above shows Dr. Machado during his presentation. On the screen an anatomical image he drew when he was 12 year old!.

Poster presentations during a coffee break

The meeting was also geared toward morphology students of different careers including Veterinary, Nursing, Dental School, and Medicine. The students presented their research posters during the coffee breaks. There were very high-quality and in-depth research, including the first osteology atlas of the Chilean flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis). I had interesting discussions on Latin terminology with these students.

There were extremely interesting topics throughout the week, including liver anatomy and liver transplant, ethics, philosophy, body donation, etc.

My presentation was based on the conference I delivered in May 2023 at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. Since the Belgium conference was delivered to a group of Andreas Vesalius experts, this one included much more information on Andreas Vesalius, his work, and additional information on printing techniques circa 1550.

Dr. Miranda during his presentation at the

XLIII Anatomy Meeting in Chile

The presentation added information on the history of the woodblocks used to print the 1543 Fabrica, the 1555 Fabrica, as well as other books that include the 1925 "The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius" by M.H. Spellman, and the 1934 Icones Anatomicæ.

The included picture was taken towards the end of my presentation where with the help of Dr. Uribe we unveiled Giovanni Paolo Mascagni's (1755-1815) work. At the center is a life-size copy of one of the pages of his book "Anatomiæ Universæ Icones", published in 9 installments between 1823 and 1832. It is important to note that each page of this book was hand-colored by Antonio Serantoni (1780-1837), thus the time it took to print and publish this book.

Mascagni's book, the largest book ever printed, shows in separate pages one third of a larger, life-size individual. Because of the rarity and value of this magnificent work, it cannot be cut and pasted.There are 16 know copies of Mascagni's anatomical opus magnus in the world, one of them at the University of Cincinnati, Ohio. USA.

With the help of Mr. Gino Pasi curator of the Henry Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions, and the help of Mrs. Samantha Scheck, graphic designer, we measured and scanned some pages of the "Anatomiæ Universæ Icones", cleaned the background (no changes were done to the image itself) and pasted them digitally. The result is a life-size male 5.9 ft tall (1,75 mt). The images are incredible, and having traveled back and forth to Belgium and Chile, they are now part of my personal library.

Once again, my thanks to my old and new friends for making my stay so interesting, both personally and professionally. My thanks to the organizers of these meetings and symposia:

Dr. Juan Carlos López Navarro

President XLIII Chilean Anatomy Meeting

Director Morphology Department - Universidad de Los Andes

Dr. Andrés Riveros Valdés

President I Latin American Clinical Morphology Meeting

Professor - Universidad San Sebastián

Dra. Viviana Toro Ibacache

President Scientific Committee

Professor - Universidad de Chile

Dr. Emilio Farfán Cabello

President Chilean Anatomy Society

Professor - Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

- Details

Normally, the heart is a midline structure found just posterior to the sternum where 35-40% of the heart mass in the right side of the thorax (chest), and the rest (60-65%) is in the left side of the thorax. In this normal condition the apex of the heart faces slightly inferior and to the left. In fact, there are many books and websites that state (wrongly) that the heart is normally in the “left side of the chest”.

If the above mentioned situation is reversed, we are in the presence of dextrocardia, that is, the heart is still in the midline, but most of the mass of the heart is in the right side of the thorax, and the apex points inferiorly and to the right.

The word dextrocardia is a derivate of the Latin [dexter], meaning “right”, and the Greek term [kardia], meaning “heart”. The word dextrocardia literally means “right-sided heart”.

Dextrocardia is a congenital condition, can be completely asymptomatic and present as an isolated condition. It can also be part of a complex genetic condition called “situs inversus” where the whole body is a mirror image of itself and all organs, including the heart are mirrored. A complete situs inversus is rare, but when present it usually does not cause problems.

The problems start when only part of the body and organs are reversed and others are not, causing an incredible number of potential anatomical variations and associated problems.

The prevalence of dextrocardia is about 1 in 12,00 pregnancies. The reported incidence is about 0.22%. Depending on the situation, dextrocardia can present with additional cardiac congenital disorders.

Sources:

1. “Dextrocardia: an incidental finding” Yusuf SW, Durand JB, Lenihan DJ, Swafford J. Tex Heart Inst J 2009;36(4):358-9.

2. Garg N, Agarwal BL, Modi N, Radhakrishnan S, Sinha N. Dextrocardia: an analysis of cardiac structures in 125 patients. Int J Cardiol 2003;88(2–3):143–56

3. Bernasconi A, Azancot A, Simpson JM, Jones A, Sharland GK. Fetal dextrocardia: diagnosis and outcome in two tertiary centres. Heart 2005;91(12):1590–4.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

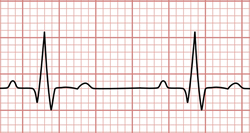

Sinus rhythm electrocardiogram

A contraction, from the Greek [συστολή] (systolí) meaning “contraction”, also [συστελλει] (systellei) meaning “to shrink, to shorten, or to draw together”.

It refers to the contraction of the heart. If you analyze a normal heartbeat (sinus rhythm), there are two systoles: an atrial systole, followed by a short interval, followed by the ventricular systole. The term systole is usually used in reference to the ventricular systole.

Systole is part of the normal rhythm of the heart and was first recognized and named by Herophilus of Alexandria (325-255BC), most probably trough animal vivisection. Herophilus was accused of animal vivisection and the dissection of human cadavers. Because of this, some call Herophilus "The Father of Anatomy".

Galen of Pergamon (129AD - 200AD) used the term [συστελλεσθαι] meaning “contracted”.

The word in English was first used in the 16th century and was originally written as “sistole”, with an "i" instead of the accepted use today with a "y". The modern pronunciation in English follows the Greek pronunciation by ending the word in a long “e” as in “to be”.

Sources

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

3. "Dorlands's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" 26th Ed. W.B. Saunders 1994

4. "Greek anatomist Herophilus: the father of anatomy" Si-Yang, N. Anat Cell Biol. 2010; 43(4): 280–283

Note: Google Translate includes an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

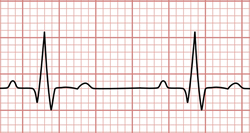

Sinus rhythm electrocardiogram

Sinus Rhythm (SR), also known as Normal Sinus Rhythm (NSR) is the term used to denote normal cardiac activity. A normal beating heart is in sinus rhythm.

In the normal beating of the heart the left and right atria contract almost simultaneously, followed by the contraction of the left and right ventricles. These atrial and ventricular contractions are separated by a lag time of 1/10th of a second which allows the atria to relax (atrial diastole) while the ventricles contract (ventricular systole). The addition of the normal action of the four heart valves (tricuspid, mitral, aortic, and pulmonary) allows the heart to work as a blood pump and circulate blood within the heart and through the body and lungs.

NSR is coordinated by a complex set of structures. The first part is the conduction system, composed of heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) which are characterized by automaticity. It is important to state here something that is known, but many times ignored: The conduction system is not composed of nerves... it is formed by specialized cardiac muscle cells! The description of this cardiomyocyte-based system can be read in a separate article here.

The second component is the cardiac autonomic nervous system (CANS), which acts as a moderator (accelerating or slowing) the cardiomyocyte-based conduction system. The CANS has two components, an extrinsic component formed by nerves and ganglia outside the heart, and an intrinsic component of nerves and ganglia that forms a complex network within the superficial aspect of the heart muscle and fat surrounding the heart. These are the cardiac ganglionated plexuses, and their dysfunction can cause abnormal heart rhythm.

Both these systems, the conduction system, and the CANS form a complex cardiac rhythm control system. For more information click here.

When these two components and their thousands of cardiac muscle cells, ganglia, and nerves are working property, the heart is in sinus rhythm, and beats between 60 to a 100 times per minute.

Personal note: The term Normal Sinus Rhythm (NSR) is redundant. By definition, if the heart is in SR, it is normal. On the other hand, the term Abnormal Sinus Rhythm is also not correct… if the heartbeat is abnormal, the heart is not in SR! (Dr. Miranda)