Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 2216 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

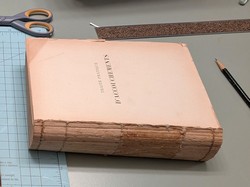

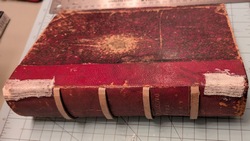

I recently received a book from Chile. This book is in French and is titled “Traité D’Accouchements” (Treatise of Childbirth) or a “Treatise in Obstetrics” and was published in 1898 in Paris. The author is Dr. Pierre-Victor Alfred Auvard, (1855 - 1940), a French Obstetrician and Gynecologist.

The book belonged to the library of San José Hospital. The Old San José Hospital is a former hospital located on San José Street, next to the General Cemetery of Santiago, in the Independencia district of Santiago, Chile. Built between 1841 and 1872, it functioned as a hospital until 1999, when the new San José Hospital was built. Parts of this hospital are now being demolished and a new one will be built in its place, but the old books from the library were discarded without a second thought. An engineer in charge of the new construction managed to rescue some of these books, and one of them was brought from Chile to the United States by another friend of mine, Carlos Verdugo, a classmate.

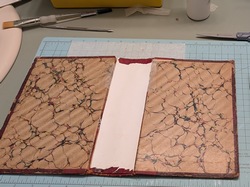

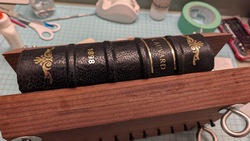

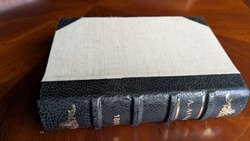

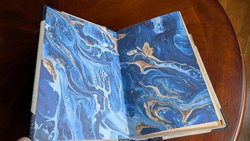

The book was in terrible condition, with a barely legible title, the spine was broken, and the signatures (groups of pages that together from the text block) separated as the threads that kept the book together were torn. Bookbinding and book repair being another one of my hobbies, I undertook the task and now it will be added to my collection. Here are some pictures of the process. Click on the image to see a larger version.

In one of its pages, the book has an old and barely legible stamp the reads “Manuel Casanueva del C.” A short search indicated that this was the Ex-Libris stamp of a Chilean surgeon Dr. Manuel Casanueva del Canto. Of course, I had to do some research on the past owner of this book.

Manuel Casanueva del Canto was born in the city of Linares, Chile on July 5, 1908. From 1925 to 1931 he coursed 1st to 6th year of medical school at the Medical College of the University of Chile (where I studied). At that time the College of Medicine was in the Independencia neighborhood in the city of Santiago. In 1930 he obtained his medical license.

The repaired book in my library

Between 1930 and 1931 he was a surgical resident at the Hospital San Francisco de Borja (where I was a patient as a child), passing through Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine and Surgery, and Obstetrics, obtaining his surgical degree in May 1932. His thesis for the degree was entitled “Pathological Anatomy: Inflammatory alterations of the gallbladder”.

As a surgeon, he worked at the Santiago Military Hospital, Central Emergency Services, and the Central Trauma Hospital. In 1952, going back to his roots, he moved to the Surgical Department of the University of Chile at the Hospital “Jose Joaquin Aguirre”. This hospital is on the same campus as the Medical College where he studied.

In 1955 he applied for (and obtained) the position of Professor Extraordinaire of Pathological Surgery in the Medical College of the University of Chile. At this time, he already had a great teaching career, several medical awards, authored the book “Practical Blood Transfusion” in 1939 as well as co-authored several medical books and over 81 papers.

He became Chief of Surgery at the Jose Joaquin Aguirre Hospital and in 1961 he invited Pablo Neruda, Chilean Nobel Prize winner in literature, to lecture at the hospital.

In 1975 Editorial Andres Bello published his book “Surgery”, two volumes in Spanish. I have not been able to trace this book. Not much is known of him after this date. No photography or portrait has been found.

He married Maria Yolanda Carrasco Coral (date unknown), they had three children: Maria Cristina, Isabel, and Manuel Luis.

He died on February 13, 1981, in the city of Viña del Mar, and is buried in Santiago, Chile. Further research indicated that this book I received as a gift was donated to the library of Hospital San José by Dr. Casanueva where it eventually was discarded, rescued, transported to the US, and repaired.

I hope this article reaches the Casanueva del Canto family in Linares (today they probably are Casanueva Carrasco and/or Casanueva Iommi) and they can help me update this research, and hopefully a photograph of Dr. Casanueva del Canto. To this end, here is the Spanish version of this article.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 5806

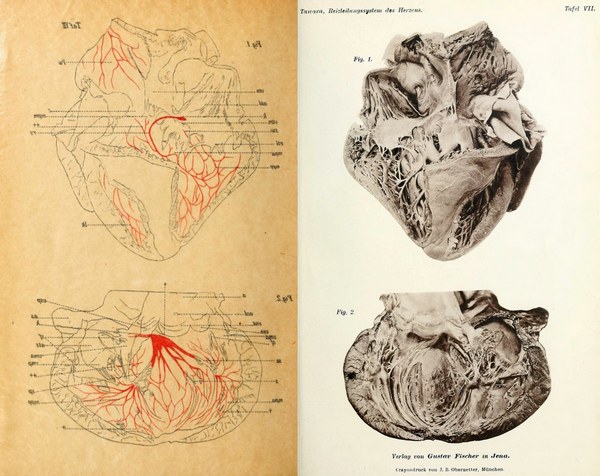

Figure 1: AV node as depicted by Sunao Tawara

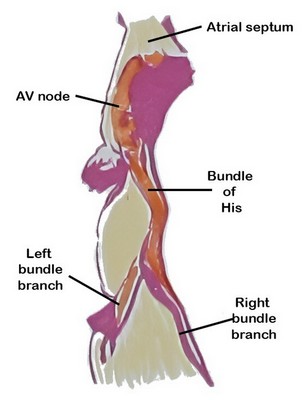

The atrioventricular (AV) node is a critical component of the conduction system of the heart, serving as the only (normal) electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles. By delaying atrioventricular transmission by 1/10th of a second, the AV node allows the heart to work as a pump.

The AV node is situated in the inferior portion of the interatrial septum. It was discovered in 1906 by Sunao Tawara, who identified it as a discrete small structure located at the atrioventricular junction and demonstrated continuity of the AV node with the His–Purkinje system (see image 1).

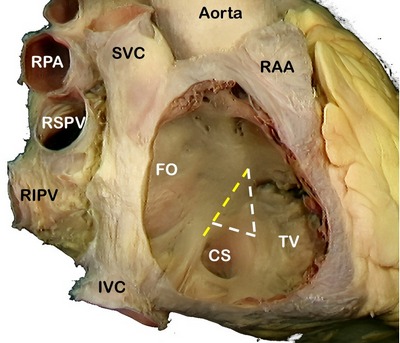

The AV node is a located in the “Triangle of Koch” (see note), a region bound by the tendon of Todaro, the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, and the ostium of the coronary sinus (see image 2). Its blood supply is by way of the AV node artery, a branch of the right coronary artery (RCA) that arises usually at the crux cordis, the point of division of the RCA into the posterior descending artery and posterolateral artery.

Image 2: SVC: Superior vena cava, RPA: Right pulmonary artery, RSPV: Right superior pulmonary vein, RIPV: Right inferior pulmonary vein, IVC: Inferior vena cava, RAA: Right atrial appendage, FO: Foramen ovale, TV: Septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve. The yellow line shows the location of the "Tendon of Todaro". The complete triangle is the triangle of Koch.

The ventricles are isolated from the atria by connective tissue that forms an electrical barrier between. This barrier is sometimes called the “skeleton of the heart” a misnomer that does not explain the reason for its presence. If there was no barrier, the atria and ventricles would all contract at the same time and the pumping action of the heart would not exist.

The only place where the electrical impulse can pass from the atria to the ventricles is through the AV node. Because of the specialized cardiomyocytes that form the node, the transmission of the impulse is delayed by one tenth of a second, enough that the ventricles will contract after the atria contract, causing blood flow through the heart.

Note: The "triangle of Koch" is eponymically named after Walter Eduard Carl Koch (1880 - 1962) a German physician, anatomist, and pathologist.

Sources and References:

1. Markowitz, MM; Lerman BL. A contemporary view of atrioventricular nodal physiology. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018 Aug;52(3):271-279.

2. Efimov IR, Nikolski VP, Rothenberg F, Greener ID, Li J, Dobrzynski H, Boyett M. Structure-function relationship in the AV junction. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004 Oct;280(2):952-65.

3.Fumarulo I, Salerno ENM, De Prisco A, Ravenna SE, Grimaldi MC, Burzotta F, Aspromonte N. Atrioventricular Node Dysfunction in Heart Failure: New Horizons from Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Perspectives. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2025 Aug 15;12(8):310.

4. Anderson RH, Sánchez-Quintana D, Nevado-Medina J, Spicer DE, Tretter JT, Lamers WH, Hu Z, Cook AC, Sternick EB, Katritsis DG. The Anatomy of the Atrioventricular Node. J of Cardiovasc Development and Disease. 2025; 12(7):245.

5. Tawara, S. Das Reizleitungenssystem des Säugetierherzens : eine anatomisch-histologische Studie über das Atrioventrikularbündel und die Purkinjeschen Fäden 1906 J Fischer pub. courtesy of archive.org

6. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

7. Anderson, Robert H. MD; Becker, Anton E. MD. "Slide Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy" 10 volumes London: Gower Medical Publishing, 1985. (out of print)

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

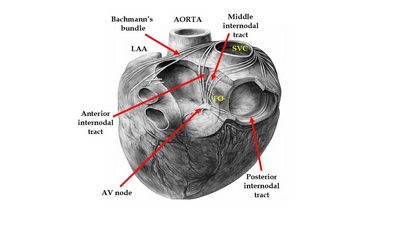

While the components of the conduction system of the heart were all described by now-famous researchers (Sunao Tawara, Wilhelm His Jr, Arthur Keith, Martin Flack, Jan Evangelista Purkinje, Jean George Bachmann), the pathway(s) of the electrical impulses from the sinoatrial (SA) node to the atrioventricular (AV) node have been historically controversial.

Once again, it must be stressed that the conduction system of the heart is not formed by nerves, but rather by specialized cardiomyocytes. The speed of the electrical depolarization of these cells is affected by their structural organization. If the cells are organized in a random, mesh-like style, the flow of electricity will be slow. If these cells are parallel to each other, the flow will be faster.

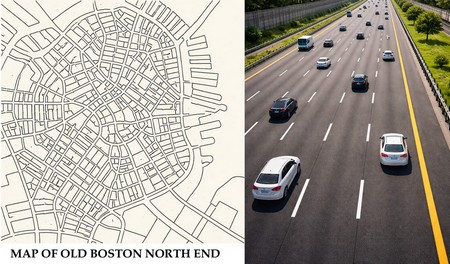

An analogy of this organization can be made by how slow it is to drive in the streets of Old Boston North End versus driving in a five-lane highway. The parallel (anisotropic) organization of the cardiac bundles (interatrial and internodal) allow for faster impulse transmission. The concept of anisotropy refers to direction-dependent conduction velocity, with faster propagation along the longitudinal axis of myocardial fibers than across them.

In 1963 Thomas N. James MD, MACP (1926 -2010), demonstrated consistent bands of atrial myocardium connecting the SA node to the AV node. James described three principal internodal pathways—anterior, middle, and posterior. His work shifted the paradigm from diffuse conduction to anisotropically organized atrial pathways.

The interatrial and internodal tracts

The anterior internodal tract originates from the anterior margin of the SA node, curves around the superior vena cava and forms Bachmann’s bundle, first described by Jean George Bachmann (1877 - 1959) in 1916. From here the anterior internodal tract leaves Bachmann’s bundle, passes posterior to the aorta and the non-coronary sinus, descends in the anterior portion of the interatrial septum and joins the anterosuperior region of the AV node.

From the SA node the middle internodal tract curves around and posterior to the SVC and descends in the interatrial septum passing anterior to the limbus fossa ovalis to enter the superior aspect of the AV node. This tract is known eponymically as Wenckebach’s bundle, named after Karel Frederik Wenckebach (1864–1940) a Dutch physician and anatomist.

The posterior internodal tract courses from the SA node around the base of the SVC and descends in the groove between the right atrial appendage and the right atrium. At this point it forms a cord of tissue at the ostium of the RAA known as the crista terminalis, it continues along an area known as the cavotricuspid isthmus to join the posterior aspect of the AV node. This tract is known eponymically as Thorel’s bundle, named after Christen Thorel (1880 –1935) a German physician and anatomist who described this structure in 1909.

Electrical conduction in a parallel bundle can go either way (same as in an electrical cable). Because the impulses are generated in the SA node, they will go towards the AV node. James argued that because of the fiber arrangement of these internodal tracts, they form circles that can allow the electrical impulse to revert towards the SA node. He calls this a “circus movement” we call that today “reentrant circuits”. These reentrant circuits can be one of the many causes of cardiac arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation.

References:

1. His W Jr. Die Tätigkeit des embryonalen Herzens und deren Bedeutung für die Lehre von den Herzbewegungen. Leipzig, Germany: Vogel; 1893.

2. Tawara S. Das Reizleitungssystem des Säugetierherzens. Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer; 1906.

3. James TN. The connecting pathways between the sinus node and A-V node and between the right and the left atrium in the human heart. Am Heart J. 1963;66(4):498-508.

4. James TN. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system in the human heart. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1961;4(1):1-43

5. Anderson RH, Ho SY. The architecture of the sinus node, the atrioventricular node, and the internodal atrial myocardium. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9(11):1233-1248.

6. Silverman ME, Grove D, Upshaw CB Jr. Why does the heart beat? The discovery of the electrical system of the heart. Circulation. 2006;113(23):2775-2781.

7. Spach MS, Dolber PC. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1986;58(3):356-371.

8. Kistin AD. Observations on the anatomy of the atrioventricular bundle and the question of other muscular atrioventricular connections. Am Heart J. 1949;38(5):673-688.

9. Cavero, I. Holzgrefe, H Internodal conduction pathways: revisiting a century-long debate on their existence, morphology, and location in the context of 2023 best science Advances in Physiology Education 2023 47:4, 838-850 1

0. Cox JL et al Cardiac anatomy pertinent to the catheter and surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020 Aug;31(8):2118-2127.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Martin W. Flack, CBE

(1882 - 1931)

Martin William Flack, CBE (1882–1931), English physician and cardiovascular physiologist.

Born in 1882, in Borden, Kent, England. Flack studied Medicine and Surgery at Oxford University, graduating in 1908. While still a medical student at the London Hospital, Flack began his most important research under Arthur Keith’s guidance. In 1906 while examining histological glass slides of the heart of a mole, Flack identified a distinct cluster of specialized cardiac muscle cells at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. Working with Keith they realized that this was the source of the heartbeat. They termed this structure the “sino-auricular node”, known today as the sinoatrial node, and published their description in 1907, completing the anatomical mapping of the heart’s conduction system following earlier work on the atrioventricular node by Sunao Tawara.

Following this discovery, Flack continued in academia as demonstrator of physiology (1905–1911) and later as lecturer (1911–1914) at the London Hospital. He coauthored “A Textbook of Physiology” in 1919 and conducted research on the physiological responses of the sinoatrial node to temperature, mechanical stimulation, and pharmacological agents in the early 1910s, demonstrating its functional characteristics.

During World War I, Flack served on the Medical Research Council and contributed to studies concerning cardiorespiratory physiology. In 1919, he was appointed Director of Medical Research for the Royal Air Force where he conducted research on the physiological performance of pilots at high altitudes and on methods to assess pilot fitness, including cardiac and respiratory functions. His contributions to medical research and service were recognized with appointment as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)

Sources:

1. Mohr PD. Illustrations of the heart by Arthur Keith: His work with James Mackenzie on the pathophysiology of the heart 1903–1908. J Med Biogr. 2021;30(3):193–201

2. Silverman ME, Hollman A. Discovery of the sinus node by Keith and Flack: on the centennial of their 1907 publication. Heart. 2007;93(10):1184–1187.

3. Keith A, Flack M. The Form and Nature of the Muscular Connections between the Primary Divisions of the Vertebrate Heart. J Anat Physiol. 1907 Apr;41(Pt 3):172-89. PMID: 17232727; PMCID: PMC1289112.

4. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 1907;41: 172–189

5. Dawadi, P; Khadka, S. Research and Medical Students: Some Notable Contributions Made in History. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021 Jan 31;59(233):94–97

Images published in this article under SAGES permission on Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 LicenseOther images Wellcome Collection Gallerypermission on Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 477

Nota: Este artículo se publicó originalmente en Inglés en Octubre de 2025. Por correos electrónicos y comentarios recibidos, hemos decidido traducirlo al idioma español.

Durante el último año, la cantidad de imágenes anatómicas y quirúrgicas generadas por inteligencia artificial (IA) en sitios web y redes sociales (Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc.) ha crecido exponencialmente. Lo mismo ha sucedido con publicaciones y artículos de supuestos expertos dirigidos al público en general, estudiantes de medicina y profesionales de la salud. Desafortunadamente, muchos de estos contienen errores anatómicos evidentes (1). La razón de esta tendencia es una carrera sin escrúpulos por obtener más seguidores, lo que lleva a la monetización de sitios web, publicaciones, individuos o grupos.

Los autores que utilizan IA para crear estas imágenes las publican tan rápido como se producen, sin considerar la exactitud de lo que la IA crea. Sus seguidores, también sin considerar ni cuestionar el contenido o la imagen, les dan "me gusta", las comparten, copian y distribuyen en internet. Un ejemplo es la publicación científica (ahora retractada) de células madre de rata utilizando imágenes de IA. La imagen generada es de muy mal gusto, a pesar de haber sido revisada por pares y publicada. La imagen muestra una rata con genitales grandes. No puedo, en conciencia, publicarla aquí. Para más información, consulte los “Recursos” 2 y 3 (un artículo periodístico sobre el problema) y la retractación del editor.

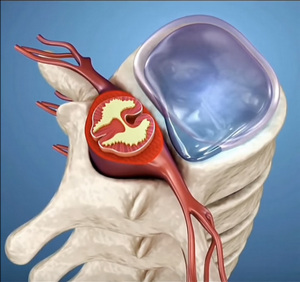

Otro ejemplo evidente es este video que muestra las válvulas cardíacas en acción. No es preciso. El movimiento y la sincronización de las válvulas son incorrectos; no se abren; la válvula pulmonar, que normalmente tiene tres valvas, muestra cuatro. Las arterias coronarias están en la ubicación incorrecta y hay una coronaria adicional en el lado derecho. ¡Nadie podría vivir con esa válvula aórtica! Sin embargo, esta imagen tiene 10 .000 «me gusta» y se ha compartido 2500 veces! Se está compartiendo ignorancia. ¡Que parezca atractiva no significa que sea correcta! (1).

El problema es que estos sitios web e imágenes están siendo utilizados por profesionales de la salud, estudiantes y grupos de capacitación de la industria médica sin cuestionar la exactitud de la información que se copia y redistribuye externa e internamente en los documentos de capacitación. Esta no es una afirmación desinformada. Lo he visto personalmente, no en una, sino en varias empresas.

La presión que tienen los grupos de capacitación en el ámbito médico y en otras industrias es reducir costos y tiempo de capacitación. Quienes me conocen y a quienes he capacitado, recordarán que hace dos décadas, la capacitación para un representante de dispositivos quirúrgicos podía durar seis, diez semanas e incluso más. ¡Conozco una empresa que exigía una pasantía de seis meses antes de considerar a alguien listo! Muchos de quienes recibieron esta capacitación ocupan hoy altos cargos corporativos o se han jubilado muy bien.

Hoy en día, se busca reducir el tiempo de capacitación presencial porque se percibe como costosa, pero el costo de una capacitación deficiente e imprecisa para una empresa es muchísimo mayor. Otras tendencias son el uso de capacitación digital (reduce costos) y la reducción de la cantidad de información que se transmite al aprendiz (reduce tiempo). Lo interesante es que dentro de estas empresas hay quienes no están interesados en aprender más, solo en capacitarse lo suficiente para realizar un trabajo básico.

Otra tendencia alarmante es que los conocimientos adquiridos en la formación se orientan a aprobar los tests internos (cumplir con los requisitos) y no necesariamente a su aplicación práctica al interactuar con un profesional médico.

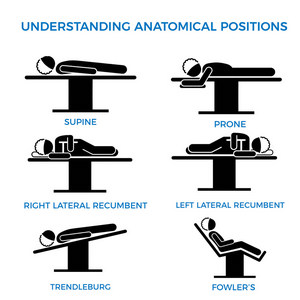

La necesidad de generar material de formación obliga a muchos a copiar y pegar imágenes y conceptos desde la Internet. Que un concepto esté disponible en Internet no significa que sea correcto. De hecho, existen muchos sitios web y libros de buena reputación que contienen información errónea. Aquí hay un ejemplo de una empresa de dispositivos médicos que muestra "posiciones anatómicas" (solo hay una posición anatómica) cuando la imagen debería estar etiquetada como "posiciones quirúrgicas". Si hace clic en la imagen, verá una imagen más grande con correcciones (en inglés).

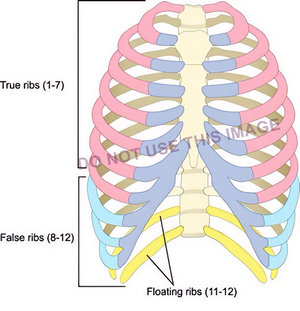

La siguiente imagen, de un ilustrador médico de buena reputación, muestra los grupos de costillas, pero hay un error: ¡Las costillas falsas son solo del 8 al 10, no del 8 al 12! Sin embargo, esta imagen se está utilizando para entrenamiento. Desconozco si fue etiquetada incorrectamente por un tercero.

He visto a muchas empresas asignar a un representante de ventas, gerente, ingeniero u otro empleado la responsabilidad de desarrollar presentaciones y capacitación en informática, ¿y qué hacen? Buscan información en internet. Aquí es donde ese acrónimo informático se convierte en una dolorosa realidad: GIGO (Garbage In – Garbage Out) basura que entra, basura que sale. Para mí, esto es inaceptable, ya que podría afectar a un paciente.

La única manera de garantizar que la información sea correcta es recurrir a un experto (aunque esto , por supuesto, no es gratis). Esto conduce a otro problema: el efecto Dunning-Kruger. Se trata de un fenómeno en el que algunas personas se creen mucho más competentes, con más conocimientos o capaces de lo que realmente son. Además, convencen a sus compañeros y a su empresa de ello. David Dunning y Justin Kruger, en su artículo de 1999, acuñaron el término "incompetente e inconsciente de ello", que lamentablemente se está volviendo común hoy en día.

Otro ejemplo de estas imágenes generadas por IA es esta vista de la columna vertebral, la médula espinal, los nervios raquídeos y sus ramas. Las articulaciones cigopofisarias parecen fusionadas (no lo están), el saco dural (tecal) llena el canal vertebral (no lo hace), el nervio raquídeo y sus ramas están mal dibujadas. Curiosamente, cuando le comenté los errores de la imagen al autor. La respuesta que recibí fue: "Cuanto más fácil sea la ilustración, más les interesará a los estudiantes. Un video complejo y con mucha información puede asustar a los estudiantes de primer año. Por eso publico las cosas de forma sencilla". Entonces, ¿es correcto enseñar algo incorrecto? Llámenme anticuado, pero no lo creo.

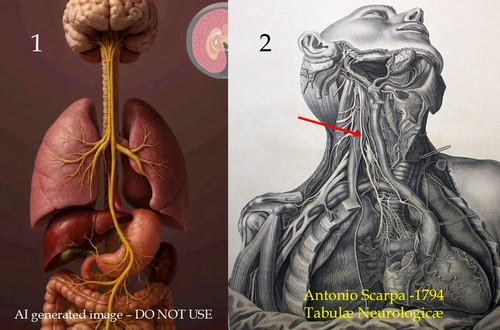

Podría seguir con estos ejemplos. Por ejemplo: La Imagen 1 es una imagen generada por IA del nervio vago. ¡Es un error en muchos sentidos! Compárese con la imagen 2, que es de dominio público y pertenece a las “Tabulae Neurologicae” de 1794 de Antonio Scarpa. La flecha muestra el nervio vago derecho..

El texto disponible en línea no debe copiarse sin asegurarse de que sea correcto. Un ejemplo: “Los pulmones están rodeados por los sacos pleurales, que están unidos al mediastino”. La primera parte es correcta: cada pulmón está contenido en un saco pleural separado (solo el 86 % de las veces; el resto de nosotros podemos tener comunicación entre ambos sacos pleurales). ¡Pero los sacos pleurales no están unidos al mediastino! El mediastino es un concepto, un espacio. La región entre los sacos pleurales no es una estructura real.

Por último, existen problemas de derechos de autor, donde se ha vuelto tan fácil resaltar, copiar y pegar que muchos no dudan en usar texto e imágenes de propiedad intelectual sin considerar las consecuencias de esta actividad. Uno de los libros más usados y abusados es el Atlas de Anatomía Humana de Frank Netter. Se puede ver por todo Internet en publicaciones diarias. Esta es una técnica para aumentar el tráfico y los clics. El hecho de que se haya publicado en una de estas redes sociales no significa que podamos usarlo libremente en materiales de formación. Este abuso es rampante en redes sociales, donde supuestos expertos copian y pegan imágenes de libros y otros sitios web.

Además, estos "expertos" generan vídeos (cuyo único objetivo es obtener un clic) que utilizan pistas de audio (probablemente también generadas por IA a partir de texto) para asustar y engañar a la gente en redes sociales.

La Internet es una herramienta extremadamente poderosa, pero es importante recordar que no todo lo que hay en Internet es verdadero, preciso, ni está fácilmente disponible para copiar y pegar. No toda la información debe creerse al pie de la letra. Espero sinceramente que esta tendencia cambie.

¿Por qué creo que esto es tan importante? En la industria de dispositivos médicos, nuestra principal responsabilidad es con el paciente y poder brindar la mejor atención. Una sana desconfianza hacia toda la información que usamos, así como la inversión de tiempo y recursos en lograr precisión, nos ayudarán a alcanzar este objetivo.

A continuación, se presentan algunos ejemplos adicionales, algunos tan falsos que resultan risorios, pero alguien los observa y cree lo que ve y oye.

El primer video muestra estructuras inferiores al colon transverso que no existen; además, los movimientos peristálticos no son así... ¡parecen más bien contracciones cardíacas! El segundo video muestra una glándula tiroides en movimiento, ¡y las estructuras vasculares y nerviosas están completamente equivocadas! ¡El tercero es ridículamente erróneo! Estos videos tienen subtítulos en español, pero se pueden encontrar en cualquier otro idioma.

Nota personal: He intentado evitar identificar a personas, sitios web, empresas, etc. al escribir este artículo. También he decidido añadir los conceptos en este articulo a lista de disgustos personales. Si quiere leer este articulo en Ingles haga clic aqui.

"El problema del mundo es que los tontos y los fanáticos siempre están tan seguros de sí mismos, mientras que la gente más sabia está llena de dudas."

Bertrand Russel

Sources:

1. “It looks sexy, but it is wrong. Tensions in creativity and accuracy using genAi for biomedical visualization” Zimman, R; Saharan, S; McGill, G; Garrison, L. 2025 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.14494

2. “RETRACTED “Cellular functions of spermatogonial stem cells in relation to JAK/STAT signaling pathway” Guo,X; Dong, L; Hao, D. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2024 PDF Link here

3. “AI-generated nonsense about rat with giant penis published by leading scientific journal” The Telegraph, 2024.

4. “Emotionally unskilled, unaware, and uninterested in learning more: Reactions to feedback about deficits in emotional intelligence” Sheldon, O. J., Dunning, D., & Ames, D. R. (2014). Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034138

5. “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments” Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

6. “Chapter 5- The Dunning–Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One's Own Ignorance” Olson, HM; Zanna, MP. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (2011) – 44: 247-296 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00005-6 (these are snippets, not the whole chapter)

7. "How people are being tricked by deepfake doctor videos on social media" New York Post July 17, 2024

8. "Positioning in Anesthesia and Surgery" Martin, JT; Warner, MA 3rd Ed. 1997 USA W.B. Saunders

9. https://elearningdoc.com/the-hidden-costs-of-inadequate-training/

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 11227

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

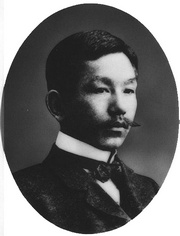

Sunao Tawara, MD

UPDATED: Sunao Tawara, M.D. (1873 - 1952) Sunao Tawara was born in the prefecture of Ooita, Kyushu, Japan. Adopted by an uncle (and physician), Tawara studied English and German, and went on to the University of Tokyo medical school, where he graduated an MD in 1901.

In 1903 he traveled to Marburg, Germany, where he started working under the supervision of Dr. Karl Albert Ludwig Aschoff (1866-1942), a noted pathologist. Tawara’s work led him to the discovery of what today we call the "atrioventricular node” (AV node) and the connections of the AV node and the Bundle of His by discovering the right and left bundle branches. His work with Aschoff led to the eponym of “node of Aschoff-Tawara” for the AV node. Tawara’s work also led to the understanding of the function of the Purkinje fibers. Tawara gave the entire system the name “Reitzleitungssytem” or the “conduction system” of the heart.

In 1906 Dr. Tawara published his discoveries in a German-language article entitled “The Conduction System of the Mammalian Heart — An Anatomicopathological Study on the Atrioventricular Bundle and the Purkinje Fibers”. The same year he returned to Japan and in 1908 became Professor of Pathology at the University of Kyushu until his retirement in 1933.

Not enough honors have been given to Dr. Tawara as the discoverer of some of the main components of the conduction system of the heart, such as the atrioventricular node, the left and right bundle brunches, and establishing the connection between the Bundle of His and the Purkinje fibers. William Einthoven himself cited Tawara's work as the basis to interpret an electrocardiogram.

Sunao Tawara was the sole discoverer of the AV node. Dr. Aschoff was his academic supervisor and mentor. When Tawara published his monograph, Aschoff wrote the foreword for it. At no time did he claim co-authorship of Tawara's work. The eponym "Aschoff-Tawara" node for the atrioventricular node was accepted to recognize Aschoff's support to Tawara's work.

Tawara's original monograph in German is available at archive.org. For the monograph, click here.

Sources:

1. "Sunao Tawara" Suma, K. Clin Cardiol (1991) 14; 442-443

2. "Sunao Tawara, A Cardiac Pathophysiologist" Loukas, M. et al Clinical Anatomy 21:2–4 (2008)

3. "Sunao Tawara: A Father of Modern Cardiology" Suma, K. J Pacing Clin Electrophysiol (2001) 24:1; 88- 96

Image of Dr. Tawara in the public domain after copyright expiration in 1970.