Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 200 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

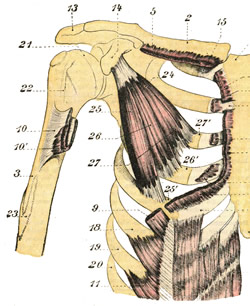

Pectoralis minor muscle (26)

Click on the image for a larger depiction

The pectoralis minor muscle is a small triangular muscle found deep to the pectoralis major in the anterior aspect of the thorax.

This muscle originates from three fleshy bellies that insert into the superior border and anterior surface of the third, fourth and fifth ribs. The muscle fibers converge superolaterally to insert into the inferomedial aspect of the coracoid process, of the scapula, where the tendon of the pectoralis minor intermingles and fuses with the tendon of the coracobrachialis muscle.

The pectoralis minor lies immediately anterior and covers some of the structures of the axillary region, the axillary artery and vein and some of the components of the brachial plexus. In fact, the pectoralis minor muscle is the landmark that divides the axillary artery into its three components: proximal (between the first rib and the medial border of the pectoralis minor). middle (deep to the pectoralis minor), and distal (between the lateral border of the pectoralis major and the inferior border of the teres major muscle). Thus defined the pectoralis major forms part of the anterior wall of the axilla.

In conjunction with other muscles, the pectoralis minor helps to maintain the scapular and shoulder joint in position. If the scapula is fixed, the pectoralis major assists to elevate the anterior thoracic wall during forced inhalation. The pectoralis minor also works as a depressor of the scapula and shoulder joint, abducts the scapula, and rotates the scapula.

The pectoralis minor is innervated by the medial pectoral nerve (C8.T1), a branch of the brachial plexus. Some of the fibers of the medial pectoral nerve perforate the pectoralis minor to provide nerve supply to a portion of the pectoralis major. The pectoralis minor is one of the 17 muscles that attach to the scapula.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 42nd British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 2021

4. “An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles” Bowden, B. 4th Ed. Morton Publishing. 2015

5. "Trail Guide to The Body" 4th. Ed. Biel, A. Books of Discovery. 2010

- Details

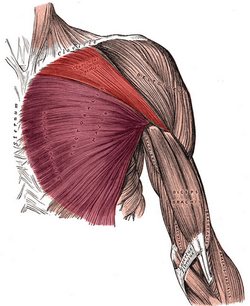

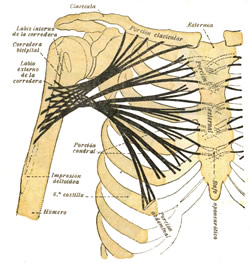

UPDATED: The pectoralis major muscle is the largest muscle in the anterior aspect of the thorax. It is thick and fan-shaped. It attaches superiorly to the medial 2/3rds of the clavicle, and medially to the anterior aspect of the sternum and cartilages of the first to sixth or seventh ribs, extending inferiorly to attach to the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Laterally, this muscle attaches to the lateral lip of the intertubercular groove (bicipital groove) of the humerus by a two-layered quadrilateral tendon which inserts each of the two heads of the muscle.

The superficial tendon attaches the clavicular head (red in the accompanying image), which extends between the intertubercular groove of the humerus and the clavicle. The deep tendon attaches the sternocostal head (purple in the accompanying image), which extends between the humeral intertubercular groove and the attachments in the sternum, costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. There is usually a well-defined interval between the two heads of the pectoralis major.

The pectoralis major is innervated by the medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1) and lateral pectoral nerve (C5-C7).

This muscle is covered by the pectoral fascia. An extension of this fascia is the clavipectoral fascia. In both male and female, the mammary gland is situated anterior to and anchors to the pectoral fascia by a number of fascial ligaments known as "Cooper's ligaments"

When both pectoral heads contract as a unit, the muscle adducts. flexes, and medially rotates the shoulder joint and humerus, such as when swimming doing and Australian crawl. Testut & Latarjet (1931) describe three separate muscular segments to this muscle, a clavicular component, a superior sternocostal component, and an inferior sternocostal component. They state that the clavicular components is quite evident, but the other two, although difficult to see, are separate. The clavicular head draws the humerus forward, upward, and medially, such as when you reach for something in front and above you. The sternocostal head draws the humerus down, forward, and medially.

The second image in this article is from Testut & Latarjet (1931) and shows the direction of muscular fibers of the three segments of the pectoralis major.

The word pectoral arises from the Latin term "pectum" meaning "chest, breast". In its true meaning, pectoral or pectoralis refers to a "chest plate" or an "adornment of the chest".

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

4. “An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles” Bowden, B. 4th Ed. Morton Publishing. 2015

First image modified from the original by Henry VanDyke Carter, MD. Public domain. Second image from Testut & Latarjet. Public domain

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

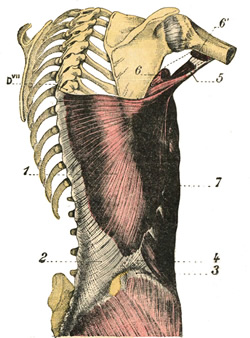

Latissimus dorsi muscle

Click on the image for a larger depiction

The latissimus dorsi muscle is a large, wide, flat muscle on the posteroinferior aspect of the back. It has the shape of a triangle that has a base at the thoracolumbar spine and its apex in the axillary region.

This muscle has a wide origin by tendons that attach to the spinous processes of the lower six or seven thoracic vertebrae as well as those of the lumbar vertebrae, the sacral crest, and the posterior aspect of the external lip of the iliac crest. This created a wide fibrotendinous lamina known as the thoracolumbar fascia. The muscle also attaches to the external surface of the three or four inferiormost ribs and the inferior angle of the scapula.

From here, the muscle fibers converge superolaterally and twist anterosuperiorly to form a quadrilateral tendon that inserts deep into the bicipital groove (Lat: sulcus intertubercularis) of the humerus as shown by number 5 in the accompanying figure. There is sometimes a tendinous extension to the humeral lesser tubercle.

The latissimus dorsi extends, adducts, and medially rotates the shoulder joint, also known as the glenohumeral joint. Along with the teres major muscle they are known as the “handcuff muscles”, as this is the action of these muscles as the hands are brought together towards the back. The latissimus dorsi is innervated by the thoracodorsal (or long subscapular) nerve (C6, C7, and C8).

The Terminologia Anatomica 2 proper name is “musculus latissimus dorsi”. The plural form is “musculi latissimi dorsi”. The name of the muscle is derived from Latin. Since “latum” means “wide”, “musculus latissimus dorsi” means the “widest muscle of the back”, quite a proper name. In other languages this is more evident. In Spanish, the name for the muscle is [músculo dorsal ancho] meaning the “wide muscle of the back”.

The latissimus dorsi is one of the 17 muscles that attach to the scapula. It also forms one of the borders of the lumbar triangle of Petit, potential site for a lumbar hernia.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 42nd British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 2021

4. “An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles” Bowden, B. 4th Ed. Morton Publishing. 2015

5. "Trail Guide to The Body" 4th. Ed. Biel, A. Books of Discovery. 2010

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 44255

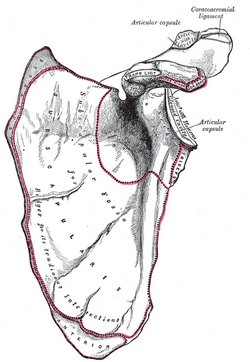

Anterior view of the left scapula.

UPDATED: The scapula is a flat, triangular bone that forms the posterior portion of the shoulder girdle. It is described with two surfaces, three borders, and three angles. The scapula attaches to the clavicle by way of the acromioclavicular joint and ligaments. . Seventeen muscles attach to the scapula and are listed here alphabetically:

1. Biceps brachii

2. Coracobrachialis

3. Deltoid

4. Infraspinatus

5. Latissimus dorsi

6. Levator scapulae

7. Omohyoid (inferior belly)

8. Pectoralis minor

9. Rhomboid major

10. Rhomboid minor

11. Serratus anterior

12. Subscapularis

13. Supraspinatus

14. Teres major

15. Teres minor

16. Trapezius

17. Triceps brachii (long head)

By surfaces, borders, and structures, these muscles group and attach as follows:

Posterior surface:

1. Supraspinatus

2. Infraspinatus

3. Teres major

4. Teres minor

Scapular spine and acromion:

5. Trapezius

6. Deltoid

Anterior surface:

7. Subscapularis

8. Serratus anterior

Medial border:

8. Serratus anterior

9. Rhomboid major

10. Rhomboid minor

11. Levator scapulae

Superior border:

12. Omohyoid (inferior belly)

Medial border:

13. Triceps brachii (long head)

External angle:

14. Biceps brachii (long head)

Coracoid process:

14. Biceps brachii (short head)

15. Coracobrachialis

16. Pectoralis minor

Inferior angle:

17. Latissimus dorsi

Note: Because the long and the short head of the biceps brachii attach to different locations of the scapula, some authors and Internet websites say that there are 18 muscles that attach to the scapula. I do not agree, as the biceps brachii is a single muscle that happens to have two separate attachments to the scapula. It would be different if this article was titled "Name the 18 separate muscular attachment points of the scapula". Dr. Miranda

Sources:

1. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

Image in the Public Domain, by Henry Vandyke Carter - Gray's Anatomy

- Details

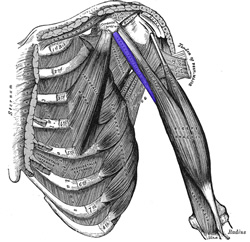

Coracobrachialis muscle.

Click on the image for a larger depiction

The coracobrachialis muscle is a thin, elongated bilateral flexor muscle that extends between the coracoid process of the scapula and the humerus bone. It is the shortest of the three muscles that attach to the coracoid process, the others being the pectoralis minor muscle and the tendon of the short head of the biceps brachii muscle. The coracobrachialis muscle attaches by way of a tendon into the middle third of the medial surface of humerus between the origins of the triceps brachii and brachialis. Its tendon mixes with the tendon of the pectoralis minor.

The coracobrachialis id one of the three muscles contained in the anterior compartment (flexor compartment) of the arm, the other two being the brachialis and the biceps brachii.

The coracobrachialis muscle helps to flex and adduct the arm as well as to stabilize the shoulder joint, helping prevent dislocation. It receives innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C7). This nerve, as it continues distally pierces the muscle and appears on its anterior aspect coursing inferiorly, The muscle is used when you reach with your hand and forearm to the contralateral aspect of your body, as in reaching to scratch your opposite ear, or doing a bench press.

It is found deep to the pectoralis major and anterior to the axillary artery and the brachial plexus. Along with the humerus and the short head of the biceps brachii, the coracobrachialis muscle forms the lateral wall of the axilla.

The coracobrachialis is one of the 17 muscles that attach to the scapula.

Note: The side image modified from the original in "Gray's Anatomy" by Henry VanDyke Carter, MD. Public domain. Animated image below by Wikimedia Commons - Anatomography [CC BY-SA 2.1 following Creative Commons attributes.

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 42nd British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 2021

4. “An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles” Bowden, B. 4th Ed. Morton Publishing. 2015

5. "Trail Guide to The Body" 4th. Ed. Biel, A. Books of Discovery. 2010

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

William J. Larsen, PhD (1942-2000). An American scientist, Dr. Larsen was a gifted scientist, consistently producing research at the forefront of cell, developmental, and reproductive biology. Early in his career he published a landmark paper that conclusively established mitochondrial fission as the mechanism of mitochondrial biogenesis. He went on to become the first to demonstrate the endocytosis of gap junctions. Moreover, his work on the hormonal regulation of gap junction formation and growth culminated in an authoritative review article in Tissue and Cell, “Structural Diversity of Gap Junctions (1988)”, which became a citation classic.

Throughout his 25 year teaching career, his sixty-seven peer reviewed publications—not to mention numerous invited reviews, abstracts, and book chapters—covered a wide range of research areas including adrenal cortical tumor cells, human ovarian carcinomas, preterm labor, cumulus expansion, oocyte maturation, ovulation, folliculogenesis, and in-vitro fertilization.

In addition to his many contributions to basic research, Dr. Larsen loved to teach and was much appreciated by his students. His exceptional ability was reflected in the four teaching awards he received as a professor at the University of Cincinnati.

Notably, he was the author of Human Embryology, a textbook for medical students that was the first to incorporate modern experimental research into a subject that had traditionally been taught in a strictly descriptive style. On its initial publication in 1998 it was hailed as, “a magnificent book…” by the European Medical Journal. With the release of the fourth edition in 2008, the book was renamed “Larsen’s Human Embryology” in recognition of Dr. Larsen's place as the originator of this revolutionary text. This book is today in it's 6th Edition.

His stellar scientific career would be enough for most people, but Dr. Larsen pursued his numerous and varied interests with such extraordinary passion, energy, and skill that he seemed to have more hours in a day than the ordinary person. He was fascinated with the American Southwest and studied and collected traditional arts and crafts of the Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo peoples. He was a woodworker who built three harpsichords and a fortepiano for his wife, and, with his two children, over 100 pieces of gallery-quality furniture. In addition, he loved to regale his friends, colleagues, and students with jokes and stories, and to share his love for gourmet cooking.

The William J. Larsen Distinguished Lecture Series

An annual lecture series was created for the Department of Cancer & Cell Biology at the University of Cincinnati to honor Dr. Larsen's research which was at the forefront of cell developmental and reproductive biology. This series recognizes forward-thinking research scientists in the field of developmental biology and asks that they share their research and findings with students and faculty of the University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine.

Personal note: I had the opportunity to meet and attend Dr. Larsen’s embryology lectures as he and I worked in the Anatomy, Embryology, and Histology program at the University of Cincinnati Medical College. Unfortunately, I never had the opportunity to have Dr. Larsen sign my personal copy of his book. He is sorely missed, Dr. Miranda

Sources:

1. "The William J. Larsen Distinguished Lecture Series" University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine.

2. https://www.larsenbooks.com

3. 2022 Larsen Lecture Series brochure (download here)

4. Dr. Larsen's family personal communications