Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 389 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

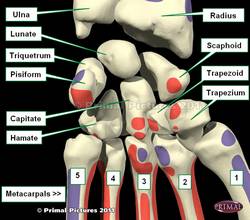

The pisiform bone is one of the four bones that comprise the proximal row of the carpus or carpal bones that form the wrist. It is the smallest of the carpal bones, is spheroidal in shape, and presents with only one articular surface (see image).

Its name originates from the Latin [pisum], meaning "pea". It is also known as "os pisiforme" or "lentiform bone", because some feel it is shaped like a lentil.

The pisiform bone articulates posteriorly with the triquetrum, and has on its anterior (volar) surface attachments to the transverse carpal ligament, and to the Abductor Digiti Quinti, and Flexor Carpi Ulnaris muscles.

The accompanying image shows the anterior (volar) surface of the wrist.

Image modified from the original: "3D Human Anatomy: Regional Edition DVD-ROM." Courtesy of Primal Pictures

- Details

This is a Latin word meaning a trench, a ditch, or an excavation. It arises from the Latine term [fodere] meaning "to dig". The plural form for "fossa" is "fossae".

There are many fossae listed in human anatomy, here are some of them:

- fossa scaphoides: found in the pinna

- fossa ovalis: found in the wall of the right atrium

- fossa triangularis: found in the pinna

- ischioanal fossa: a triangular fossa found in the perineum, inferior to the pelvic diaphragm and superior to the urogenital diaphragm, etc.

- Details

The prefix [pre-] has its origin in the Latin preposition [prae] meaning "anterior", "in front of", or "before".

Applications of this prefix include:

- precordial: anterior to the heart, as in "precordial pain"

- preoperative: before the operation

- preperitoneal: anterior to the peritoneum, referring to the region found outside and anterior to the peritoneal sac, an area containing fat, and important for preperitoneal laparoscopic surgery

- presystolic: before systole

- preaortic: anterior to the aorta

- Details

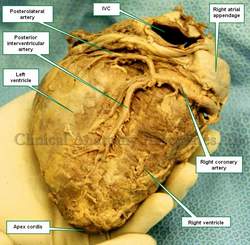

The right coronary artery usually bifurcates in an area of the posterior aspect of the heart known as the "crux cordis" giving origin to two terminal branches: the posterior interventricular artery (anatomical term) and the posterolateral artery. The posterior interventricular artery is better know to clinicians as the "posterior descending artery" or PDA.

The PDA descends towards the apex cordis where it ends. It gives off several small ventricular branches, but its most important branches are the septal perforators. These branches dive deep and provide blood supply to the posterior 1/3rd of the interventricular septum.

The AV node artery, which provides blood supply to the atrioventricular node (a component of the conduction system of the heart) may arise from the PDA instead of arising from the right coronary artery.

The PDA may present with a number of anatomical variations, including:

- arising from the circumflex artery (and absence of the posterolateral artery)

- arising from the first septal perforator of the anterior interventricular artery

- arising from the second diagonal artery

- arising from anterior interventricular artery

- being double, with one PDA arising from the circumflex artery, and another from the right coronary artery, etc.

Image property of: CAA, Inc. Photographer: E. Klein

- Details

The [circumflex artery] (CFX) is one of the two branches of the left coronary artery, the other one being the left anterior descending artery (LAD), also known as the anterior interventricular artery.

The prefix [circum-] means "around", while the root term [-flex-] means "to bend". This describes quite well the circumflex artery, which "bends around" the obtuse margin of the heart passing from the anterior surface to the posterior surface of the heart.

The circumflex artery lies deep to the epicardium in the subepicardial fatty layer. It gives off several branches, including small left atrial branches and one or two obtuse marginal arteries (OM1 and OM2)that provide blood supply to the left ventricle in its obtuse margin and posterior ventricular region, as well as a portion of the anterior papillary muscle related to the mitral valve.

There can be interesting anatomical variations in the coronary arteries of the heart. For a detail on these anatomical variations, click here. Heart and coronary artery anatomy is one of the many lecture topics presented by CAA, Inc.

Image property of:CAA.Inc.Artist:Victoria G. Ratcliffe

- Details

The prefix [post-] has its origin as a Latin adverb meaning "after". There are two variations in the use of this Latin adverb. The first is in its use as "after" referring to the position of a structure. This use is limited and is the root for the term "posterior". The most common usage is for [post-] to be used in its true meaning of "after" referring to time.

Applications of this prefix include:

- postoperative: after the operation

- postmortem: from the Latin word [mortis] meaning "death". After death

- postpartum: from the Latin word [partum] meaning "birth". After birth

- postprandial: [prandium] is a Latin word meaning "a midday meal". Used to denote "after a meal"

- posthumous: from the Latin word [humus] meaning "ground". Refers to activities performed after burial

- postbellum: after a war

When using pure Latin terms, the word can be used as shown in the listing above, or they can be used as separate entities, such as "post partum", "post mortem", "post bellum", etc. (no hyphens). This leads to interesting facts, such as the pharmacological abbreviation "p.c." which stands for "post cibum"; the meaning of [cibum] is similar to [prandium], so "p.c." means "after a meal"

![Anterior view of the heart Coronary Arteries. The [*] indicates the left coronary artery](/images/MTD/SmallImages/coronaryarterieslabels_sm.jpg)