Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 619 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

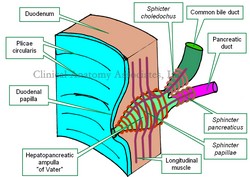

The [sphincter of Oddi] is a complex system of smooth muscles that controls flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum. Although known by its eponym, this structure has the anatomical name of "sphincter of the hepatopancreatic ampulla". Although described previously by others, it was Ruggero Oddi (1864-1913) who described not only its structure, but also its function.

The hepatopancreatic ampulla or "ampulla of Vater" is a dilation found at the conjunction and end of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct. The presence of the hepatopancreatic ampulla creates a nipple-like elevation of the duodenal mucosa called the "duodenal papilla".

The sphincter of Oddi has several components:

- Sphincter papillae: This portion of the sphincter surrounds the papillary and intramural portion of the hepatopancreatic ampulla

- Sphincter choledochus: This portion of the sphincter surrounds the most distal portion of the common bile duct. It must be noted that this is the narrowest portion of the common bile duct, allowing for potential lodging of bile stones, cause for choledocholithiasis

- Sphincter pancreaticus: This portion of the sphincter surrounds the most distal portion of the pancreatic duct and prevents reflux of bile from the hepatopancreatic ampulla to the pancreatic duct.

The duodenal muscular layer parts to allow passage of the complex formed by the hepatopancreatic ampulla and the sphincter of Oddi, creating a window called the "choledochal window". Longitudinal fibers from the duodenal muscularis externa pass and join to the sphincter of Oddi.

- Details

This is a root term of Greek origin. In both presentations [-chol-] or [-chole-] it means "bile" or "gall". The English word "gall" is of Anglosaxon origin and means "bile", referring to its yellowish-green color. The word [bile] is of Latin origin, from [bilis].

These root terms are used in many medical words, such as:

- cholecystitis: [cyst] means "sac" or "bladder", [itis] means "inflammation" or "infection". Gallbladder inflammation

- cholecystectomy: [cyst] means "sac" or "bladder", [ectomy] means "removal". Gallbladder removal

- cholangiogram: [angi] means "vessel", [(o)gram] means "examination". Examination of a bile vessel

- choledocholithiasis: Condition of stones in the bile duct. Click on the link for more information

- cholera: The suffix [-era] is "flow" or "discharge". The term refers to the constant vomiting of bile in patients afflicted with this disease. This term has been heatedly discussed and this is but one of the theories as to the etymology of the word.

In the early days of physiology, yellow bile was considered one of the "four humors" that made up human personality, temperament, and health. A person with an excess of yellow bile would be considered bad tempered, angry, or "choleric". Observe how the root term [chole] also is found in the word "choleric".

Sources:

1. "The Language of Medicine" John H. Dirckx Pub: Harper & Row 1976

2. "Medical Meanings" Haubrich, William S. Am Coll Phys Philadelphia 1997

3. "The origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, AH, 1970

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Ruggero Oddi

Ruggero Oddi (1864-1913). Anatomist and physician, his complete name was Ruggero Ferdinando Antonio Giuseppe Vincenzo Oddi Pampaglini, born on July 20, 1814 in the city of Perugia, Italy. He studied medicine in the University of Perugia, where he had a keen interest in anatomy and physiology, graduation with a medical degree in 1889. In 1887, as a fourth year medical student Oddi published a paper that would make his name eponymically tied to the sphincter found around the hepatopancreatic ampulla; what today is known as the "sphincter of Oddi". His paper was entitled "Di una Speciale Disposizione a Sfintere allo Sbocco del Coledoco" (On a Special Sphincteric Arrangement at the Outlet of the Common Bile Duct).

Although the circular muscle of the sphincter of Oddi had already been described by Glisson in 1681, Oddi was the one who did a complete anatomical and physiological study of this structure uncovering the fact that it was indeed a sphincter. He continued his studies on the hepatobiliary sphincter until 1894, when he moved to Congo and later back to Belgium.

Because of his inclination towards metaphysical studies, Oddi started experimenting with drugs on himself and became addicted.

His later life was surrounded by scandal and controversy, because of drug abuse and fiscal mismanagement of University funds. Oddi died in poverty in 1913 and his site of burial is unknown.

Sources:

1. "Ruggero Ferdinando Antonio Guiseppe Vincenzo Oddi" Lukas, M, et al. World J Surg (2007) 31:2260–2265

2. "Ruggero Oddi; To commemorate the centennial of his original article--"Di unaspeciale disposizione a sfintere allo sbocco del coledoco" Ono, K; Hada, R. Jap J Surg, VOL. 18, No. 4 pp. 373-375, 1988

3. "Ruggero Oddi: 120 years after the description of the eponymous sphincter: A story to be remembered" Capodicasa, E. J Gastroent Hepat 23 (2008) 1200–1203

4. "Oddi: The Paradox of the Man and the Sphincter" Modlin, IM; Ahlman, H. Arch Surg 129 (1994) May 550-557

Original image in the public domain, courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

- Details

The "Angle of His" refers to the normally acute angle between the abdominal esophagus and the fundus of the stomach at the esophagogastric junction.

This angle is one of the elements that are important in the prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). When the fundus of the stomach gets expanded by air, because of the normal anatomy and relations of the esophageal hiatus, the esophagogastric junction structures are "pushed" from left to right, pushing close the gastroesophageal flap valve or "rosette". There are other mechanisms that add to the sphincter-like action of the esophagogastric junction structures.

The eponym "angle of His" remembers Dr. Wilhem His Jr. (1864 -1934), a German physician and anatomist, who also described the atrioventricular bundle or "Bundle of His", one of the components of the conduction system of the heart.

Thanks to Debbie Donovan for suggesting this post.

Images property of:CAA.Inc. Artist:Dr. E. Miranda

- Details

The term [coronary dominance] is the answer to the following question: From which coronary artery does the posterior interventricular artery (PDA) arise?

In most of the human species the PDA arises from the right coronary artery, (see accompanying image), therefore most humans (70%) are right dominant. The rest are either left dominant (10%) or have balanced dominance (20%). These statistics have significant variation in different studies.

In the case of balanced dominance, there is either a double posterior interventricular artery, where one is a branch of the right coronary artery and the other a branch of the left coronary artery, or a single PDA receiving blood supply from both coronary arteries.

Coronary dominance is important because the interventricular septum receives blood supply from the PDA in its posterior 1/3rd. If the heart is left dominant, all the blood supply of the interventricular septum is dependant on the left coronary artery. In this case, blockage of the left coronary artery can be catastrophic!

There can be interesting anatomical variations in the coronary arteries of the heart. For a detail on these anatomical variations, click here. Heart and coronary artery anatomy is one of the many lecture topics presented by CAA, Inc

Image property of:CAA.Inc.. Artist:Victoria G. Ratcliffe

- Details

This is a word of Greek origin. The prefix [a-) means "absence of", or "without". The root term [-phon-] means "sound" or "voice". Aphonia is a pathological absence of voice, and was used by both Hippocrates and Galen.

Do not confuse [aphonia] with [dysphonia], where the prefix [dys-] means "abnormal". In aphonia there is total absence of voice, whereas in dysphonia there is an abnormal voice or "hoarseness"

As a side note, the word [phonograph] arises from the combination of the root terms [-phon-] and [-graph-], which means "to write". The word [phonograph] does not relate to the playing of a record, but rather to the process of creating one, transforming sound into a wavy line etched on a rotating wax model that is later cast into records. The modern production of sound CD's is similar, where the sound waves are act upon a laser that "burns" the track into a master CD. It is a similar process, but I guess calling creating a CD a type of "phonography" is too old fashion for modern marketing!

![Coronary Arteries. Coronary Arteries. The [*] indicates the left coronary artery](/images/MTD/SmallImages/coronaryarterieslabels_sm.jpg)