The ganglionated plexi are an important part of the rhythm control system of the heart. One of the problems with the concept of the ganglionated plexuses (also known as ganglionated plexi or GPs) is that these structures are rarely mentioned in medical education and are known only to specialists. People looking for information on this topic rarely find a detailed explanation. This article’s objective is to explain these structures and their function, as well as include some historical vignettes. We will start with a review of the structure and organization of the human nervous system.

The nervous system is a complex network responsible for coordinating bodily functions and maintaining homeostasis, that is, to maintain a constant internal environment despite a variable external environment. It operates as the body’s control center, enabling interaction between different parts of the body and facilitating interactions with the environment, both external and internal. It is composed of two main types of cells: neurons and neuroglia, also known as glial cells. Neurons are responsible for transmitting information through electrical and chemical signals. Glial cells support and protect neurons, also helping in their nutrition.

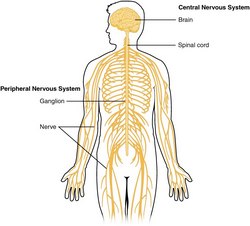

The nervous system is divided into a central nervous system (CNS) and a peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS is that portion (brain and spinal cord) contained within the craniospinal cavity and the PNS is composed of neurons and nerves outside this cavity.

It must be noted that these divisions of the nervous system are didactic, that is, they have been created to teach and understand its organization. The fact is that humans have only one nervous system.

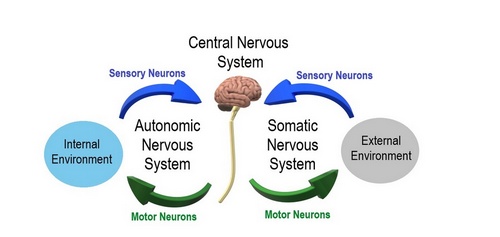

Another division of the nervous system is that of a somatic component and an autonomic component. The somatic component controls voluntary movements and conveys sensory information to the CNS. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) manages involuntary functions such as heartbeat, digestion, urination, etc. For this article we will focus on the ANS.

The ANS is further divided into a sympathetic division, which prepares the body for stress or emergencies (fight or flight response); and a parasympathetic division, which conserves energy, slows down the body and restores the body to a state of calmness (rest and relaxation). Within the ANS we will find motor (efferent) and sensory (afferent) neurons.

Within the PNS and as part of the ANS there are accumulations of neuronal bodies within or close to the internal organs of the body. Each one of these is called a ganglion (Pl. ganglia). The most recognized ganglia are those that compose the sympathetic chain and those related to the origin of most of the branches of the abdominal aorta (Superior mesenteric, celiac, renal, inferior mesenteric, etc.)

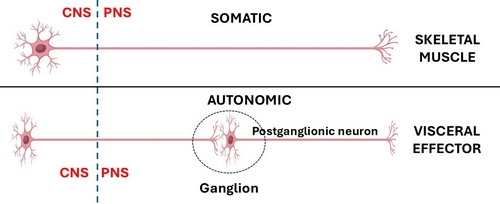

In the case of the CNS somatic (bodily, voluntary) motor organization, is composed of one neuron that is usually located in the frontal lobe motor cortex of the brain in the area known as the precentral gyrus. The distal motor effector of these neurons are distributed to striated (voluntary) muscles throughout the body.

The ANS has been classically described as a 2- neuron system. The body of the first one is found in the CNS and is called the preganglionic neuron, the body of the second one is found in a PNS ganglion and is called the postganglionic neuron, which connects to an autonomic effector (smooth muscle or glands). John Newport Langley (1852 – 1925) a British physiologist coined the terms “preganglionic” and “postganglionic”.

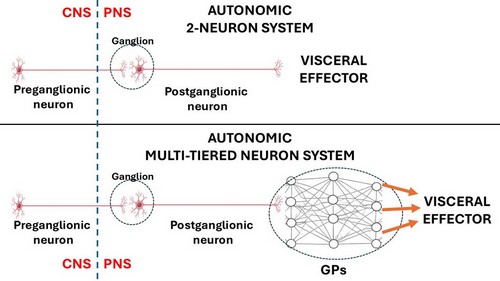

This classic 2-neuron description works for glands and some organs, but it does not consider organs that have rhythmic activity, such as the digestive system and its peristalsis, the heart, ureters, etc.

AI generated image of a neural network

The rhythmicity of these organs is so complex that it requires additional neurons within the muscle layers of each organ. These neurons are found in small intramural ganglia which interconnect with other ganglia by way of nerve fibers forming a complex meshwork (Lat: Plexus). These are the ganglionated plexi (GPs) and their function is to reduce the workload of the CNS by working mostly on their own with oversight of the CNS. These GPs have multiple interconnections forming a neural network, quite similar (on a smaller scale) to the organization of the brain.

Thus, the ANS should be considered as a 2- neuron system in cases such as glands and some organs but, in the case of rhythmic organs there will be ganglionated plexi between the postganglionic neuron and the effector, making it a multiple-tiered system depending on the number of neurons that are interconnected within the GPs.

The two most well-known ganglionated plexi are those found in the muscular and submucosal layers of the small intestine. These plexuses are also found in all the digestive system organs but are more easily studied in the small intestine. They are the plexus of Meissner (submucosal) and the plexus of Auerbach (myenteric). Together they control peristalsis, regulate local secretion and absorption, and modulate blood flow. These nerve plexuses were first described by Leopold Auerbach (1828 -1897) in 1857 and Georg Meissner (1829 – 1905) in 1864.

Because of the importance of these GPs and their activity, they have been called the “enteric nervous system” or the “little brain of the gut” by scientists and journalists. In my opinion, this moniker isolates these GPs from their function as part of the whole of the nervous system.

Another organ that has the same two-layered GPs is the ureter, as described by Pieretti (2018). Neurons (GPs) have been found in the walls of the urethra.

There are organs that have both voluntary and involuntary innervation, such as the urethra, urinary bladder, parts of the anal sphincters, etc. An interesting example of this is the respiratory diaphragm. Most of the day, we are not aware of it working (involuntary – ANS dependent), but if you want to, you can take a deep breath at will (voluntary – somatic dependent)

GPs have been described in the heart, which is a quintessential rhythmic organ. Our life depends on its rhythmicity which helps pump blood through the body. Even before the GPs were discovered, the innervation of the heart was described in detail by Antonio Scarpa (1752 – 1832) in his book “Tabulæ Neurologicæ” published in 1794.

The first to describe GPs in the heart was Robert Remak (1815 – 1865) in 1838, they were known as ”Remak’s ganglia”. Later studies were carried out by Woolard (1926), Singh (1996), Pauza (2000), and others. In these research papers great images of the neuron component of these GPs were published.

Before continuing with the topic of the GPs it is necessary to divert slightly to discuss the conduction system of the heart. The conduction system of heart has been described as a group of nodes and fibers that carry electrical impulses within the heart. (sinoatrial node, interatrial and atrioventricular bundles, atrioventricular node, bundle branches, Purkinje fibers). What is not commonly known is that this system is not formed by neurons and nerves, but by specialized cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells). Each one of these specialized cells has an automaticity that allows them to beat at a specific number of beats per minute (bpm). The further distally within the conduction system the slower the bpm of each of these muscle cells.

So, if each muscle cell has a predetermined bpm count, how does the heart rhythm increase or decrease when needed? The answer lies in complex reflexes mediated by the GPs and in the interaction of the ANS with the GPs of the heart.

The GPs and their interconnections form the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS), which has several important functions:

Heart Rate Regulation: The GPs modulate the activity of the sinoatrial (SA) node, which is responsible for initiating the heartbeat.

Conduction Modulation: The GPs also modulate the conduction pathways in the heart, particularly the atrioventricular (AV) node and Purkinje fibers, ensuring coordinated contractions of the heart muscle.

Cardioprotection: The GPs help protect the heart by altering cardiac output in response to exercise, stress, ischemia, etc., maintaining heart function and helping homeostasis under challenging conditions.

Coordinate Local Reflexes: The GPs integrate sensory information from the heart and coordinate local reflexes, allowing for rapid adjustments to changes in the heart's environment.

These functions highlight the importance of ganglionated plexuses in maintaining heart health and responding to physiological demands. Dysfunction in these plexuses can lead to various cardiac issues, including arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AFib), and heart failure.

J. Andrew Armour

Cardiac GPs are found in the cardiac wall, although most of them are found intramural and superficial (epicardially) (Tan, 2006), and also embedded in epicardial fat, in the areas devoid of pericardium (formed by the pericardial reflections) around the pulmonary veins, superior vena cava and around the ligament of Marshall. Although GPs are found in the atria and ventricles, there are 5 times more atrial than ventricular GPs (Armour, 1997).

In the study of the GPs, J. Andrew Armour MD, PhD, has been a foundational figure in neurocardiology, and his work has shaped our modern understanding of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS), and the GPs. He proposed that the ICNS is not just a passive relay for ANS signals, but a complex integrative network of efferent (motor) neurons, afferent (sensory) neurons, and local circuit neurons that form the GPs. Through his work, Armour argued that the heart’s neuronal network is sufficiently rich to process information, participate in local reflexes, and modulate cardiac function independent of central nervous system input. This can be proven by the heart working normally in heart transplants, completely separated from the recipient's nervous system.

In conclusion, there are two points to consider:

1. The 2-neuron organization of the ANS must be expanded to consider all organs that have rhythmicity and have GPs forming an intramural neural network, following this schema.

2. Our understanding of the rhythmicity of the heart has been one-sided, focusing only on the cardiomyocyte-based conduction system of the heart. This leads to surgical and minimally invasive treatments that do not consider the ICNS and GPs, as well as the location of most of the GPs on the external layers of the heart. A unified approach to these structures will certainly help those patients with cardiac arrhythmias and their surgical treatment.

Sources:

1. Stavrakis S, Po SS. “Ganglionated Plexi Ablation: Physiology and Clinical Concepts.” Heart Rhythm 2017. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 6(4):186–190

2. “The Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System and Its Role in Cardiac Function” Fedele L, et al. 2020. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 7(4):54.

3. "A brain within the heart: A review on the intracardiac nervous system" Campos, I.D.; Pinto, V.J Mol and Cell Cardiol. 2018 119:1-9

4. "Anatomical Distribution of Ectopy-Triggering Plexuses in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation" Kim, MY et al Circulation" Arrythmia and Electrophysiol 2020. 13:9

5. “Morphology, Distribution, and Variability of the Epicardiac Neural Ganglionated Subplexuses in the Human Heart” Pauza, D., Skripka, V et al The Anatomical Record 259:353–382 (2000)

6. “Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Human Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System” Armour JA et al, (1997) The Anatomical Record 247:289-298

7. “The Junction Between the Left Atrium and the Pulmonary Veins, An Anatomic Study of Human Hearts” Nathan, H; Eliakim, M. Circulation (1966) 34: 412-422

8. “Autonomic innervation and segmental muscular disconnections at the human pulmonary vein-atrial junction: implications for catheter ablation of atrial-pulmonary vein junction” Tan AY, Li H, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Chen LS, et al J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:132–143

9. “Topography of cardiac ganglia in the adult human heart” Singh S, Johnson PI, Lee RE, Orfei E, Lonchyna VA, Sullivan HJ, et al. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 112:943-53

10. Woollard, H. H. “The Innervation of the Heart.” Journal of anatomy (1926) 60 Pt 4: 345-73. 4

11 “Tabulæ Neurologicæ ad illustrandam historiam anatomicam cardiacorum nervorum, noni nervorum cerebri, glossopharyngæi, et pharyngæi ex octavo cerebri. ” Scarpa, A. 1794 Balthasarem Comini Pub.

12.“The Involuntary Nervous System” Gaskell, W. H.2nd Ed. Longman, Green & Co. 1920

13. “Cardiac anatomy pertinent to the catheter and surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation”. Cox. JL et al J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020 Aug;31(8):2118-2127. doi: 10.1111/jce.14440.

14. "Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: A New Look at an Old Problem" Randall K. Wolf, Efrain A. Miranda, Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2024,

15. “Correlative Anatomy for the Electrophysiologist: Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Part I: Pulmonary Vein Ostia, Superior Vena Cava, Vein of Marshall” Macedo PG, Kapa S, Mears JA, Fratianni A, Asirvatham SJ. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010 Jun 1;21(6):721-30.

16. “Treatment of lone atrial fibrillation: minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation, partial cardiac denervation and excision of the left atrial appendage” Wolf, R.K. Ann Cardiothoracic Surg. 2014; 3:98-104

17. “Neurocardiology: Anatomical and Functional Principles” Armour, J.A. Institute of HeartMath, Boulder Creek, CA, 2003

18. “The enteric nervous system: a little brain in the gut" Annahazi, A. ∙ Schemann, M. Neuroforum. 2020; 26:31-42

19. “The Little Brain Inside the Heart” Dr. José Manuel Revuelta Soba Professor of Surgery. Professor Emeritus, University of Cantabria, Spain

Images

Image of the CNS - Public Domain. Source: WikipediaCreative CommonsAttribution 4.0 International license.

Autonomic and Somatic Image. Public Domain by Christine Miller. Source: WikipediaCreative CommonsAttribution 4.0 International license.