This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Further to my comment on old books and research that started with an interesting bookplate (Ex-Libris). I continued my research and found that the person in charge of the Osler library bookplate was a fascinating individual that today maybe a ghost in the MedChi library and building in Baltimore... This is certainly an article that can be called "A Moment in History"

Marcia Crocker Noyes was the librarian at The Maryland State Medical Society from 1896 to 1946 and was a founding member of the Medical Library Association.[1][2][3]

Sir William Osler, MD. a famous Johns Hopkins surgeon was a noted bibliophile and had a large personal collection of books on various topics. When he became the President of MedChi in 1896, he was dismayed at the condition of the library and knew that with the right person and some stewardship, it could become a significant collection. Sir William asked his friend, Dr. Bernard Steiner, a physician and President of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore for suggestions of a librarian, and Dr. Steiner recommended Marcia Crocker Noyes. A native of New York, and a graduate of Hunter College, Marcia had moved to Baltimore for a lengthy visit with her sister, and took a “temporary” position at the Pratt Library, which turned into three years. Although she had no medical experience or background, she was enthusiastic, and most importantly, she was willing to move into the apartment provided for the librarian, who needed to be available 24 hours a day.

The image in this article is Ms. Noyes on her first year on the job. Marcia developed a book classification system for medical books, based on the Index Medicus, and called it the Classification for Medical Literature. The system uses the alphabet with capital letters for the major divisions of medicine and lower-case ones for the sub-sections. The system was used for many years, but it's now dated and the Faculty's original shelving scheme was never changed. The card catalogs still reflect her classification and many of the cards are written in Marcia's back-slanting handwriting.

Marcia knew enough to ask the Faculty's members about medical questions, terminology and literature. She gradually won over the predominantly male membership and they became her greatest allies; Sir William at the start, and then for nearly 40 years, Dr. John Ruhräh, a wealthy pediatrician with no immediate family of his own. She made a point of attending almost every Faculty function, and in 1904, under guidelines from the American Medical Association, Marcia was made the Faculty Secretary. For much of her first 10 years, she was the Faculty's only full-time employee, only being assisted by Mr. Caution, the Faculty's janitor. Later in life Marcia would say that she hired him because of his name!

Within ten years, the library had outgrown its space, and plans, spearheaded by Marcia and Sir William before his move to Oxford, were made to build a headquarters building, mainly to house the library's growing collection of medical books and journals.

Marcia was instrumental in the design and building of the new headquarters. She travelled to Philadelphia, New York and Boston to look at their medical society buildings, and eventually, the Philadelphia architectural firm, Ellicott & Emmart was selected to design and build the new Faculty building. Every detail of the building held her imprimatur, from the graceful staircase, to the light-filled reading room, and all of the myriad details of the millwork, marble tesserae, and most of all, the four-story cast iron stacks. She was on-site, climbing up unfinished staircases, checking out the progress of the building, which was built in less than one year at a cost of $90,000.

Among the features of the new building was a fourth-floor apartment for her. She referred to it as the "first penthouse in Baltimore" and it had a garden and rooftop terrace. The library collection eventually grew to more than 65,000 volumes from medical and specialty societies around the world. Journals were traded back and forth, and physicians eagerly anticipated the arrival of each new issue. At the same time, Marcia was involved in the Medical Library Association as one of eight founding members. The MLA promotes medical libraries and the exchange of information. One of the earliest mandates of the MLA was the Exchange, a distribution and trade service for those who had duplicates or little-used books in their collections. Initially, the Exchange was run out of the Philadelphia medical society, but in 1900 it was moved to Baltimore and Marcia oversaw it. Several hundred periodicals and journals were received and sent each month, a huge amount of work for a tiny staff. In 1904, the Faculty had run out of room to manage the Exchange, so it was moved to the Medical Society of the Kings County (Brooklyn). But without Marcia's excellent administrative skills, it floundered and in 1908, the MLA asked Marcia to take charge once again.

In 1909, when the new Faculty building opened, there was enough room to run the Exchange and with the help of MLA Treasurer, noted bibliophile and close friend, Dr. John Ruhräh, it once again became successful. Additionally, Marcia and Dr. Ruhräh combined forces to revive the MLA's bulletin, which had all but ceased publication in 1908, taking the Exchange with it. This duo maintained editorial control from 1911 until 1926. In 1934, around the time of Dr. Ruhräh's death, Marcia became the first “unmedicated” professional to head the MLA. During her tenure, the MLA incorporated, the first seal was adopted, and the annual meeting was held in Baltimore. Marcia wanted to write the history of the MLA once she retired from full-time work at the Faculty, but her health was beginning to fail. She had back problems and had suffered a serious burn on her shoulder as a young woman, possibly from her time running a summer camp, Camp Seyon, for young ladies in the Adirondack Mountains. In 1946, a celebration was planned to honor Marcia's 50 years at the Faculty. But she was adamant that the physicians wait until November, the actual date of her 50 years. However, they knew she was gravely ill, and might not make it until then, so a huge party was held in April. More than 250 physicians attended the celebration, but the ones she was closest to in the early years, were long gone. She was presented with a suitcase, a sum of money to use for travelling, and her favorite painting of Dr. John Philip Smith, a founder of the Medical College in Winchester, Virginia. It was painted by Edward Caledon Smith, a Virginia painter who had been a student of the painter Thomas Sully.[4] She adored this painting and vowed, jokingly, to take it with her wherever she went.

In 1909, when the new Faculty building opened, there was enough room to run the Exchange and with the help of MLA Treasurer, noted bibliophile and close friend, Dr. John Ruhräh, it once again became successful. Additionally, Marcia and Dr. Ruhräh combined forces to revive the MLA's bulletin, which had all but ceased publication in 1908, taking the Exchange with it. This duo maintained editorial control from 1911 until 1926. In 1934, around the time of Dr. Ruhräh's death, Marcia became the first “unmedicated” professional to head the MLA. During her tenure, the MLA incorporated, the first seal was adopted, and the annual meeting was held in Baltimore. Marcia wanted to write the history of the MLA once she retired from full-time work at the Faculty, but her health was beginning to fail. She had back problems and had suffered a serious burn on her shoulder as a young woman, possibly from her time running a summer camp, Camp Seyon, for young ladies in the Adirondack Mountains. In 1946, a celebration was planned to honor Marcia's 50 years at the Faculty. But she was adamant that the physicians wait until November, the actual date of her 50 years. However, they knew she was gravely ill, and might not make it until then, so a huge party was held in April. More than 250 physicians attended the celebration, but the ones she was closest to in the early years, were long gone. She was presented with a suitcase, a sum of money to use for travelling, and her favorite painting of Dr. John Philip Smith, a founder of the Medical College in Winchester, Virginia. It was painted by Edward Caledon Smith, a Virginia painter who had been a student of the painter Thomas Sully.[4] She adored this painting and vowed, jokingly, to take it with her wherever she went.

The painting was not to stay with her for very long, for she died in November 1946, and left it to the Faculty in her will. Her funeral was held in the Faculty's Osler Hall, named for her dear friend. More than 60 physicians served as her pallbearers, and she was buried at Baltimore's Green Mount Cemetery. In 1948, the MLA decided to establish an award in the name of Marcia Crocker Noyes. It was for outstanding achievement in medical library field and was to be awarded every two years, or when a truly worthy candidate was submitted. In 2014, the Faculty began giving a bouquet of flowers to the winner of the award in Marcia's name, and in honor of her work. Much evidence exists for this tradition, as we know that the physicians, especially Drs. Osler and Ruhräh, frequently gave her bouquets of flowers. Marcia also cultivated flower gardens at the Faculty and decorated the rooms with her work.

Today, the MedChi building is open for tours and if the rumors are to be believed Ms. Marcia Crocker Noyes is still at work in her beloved library as the "resident ghost" [1][5]

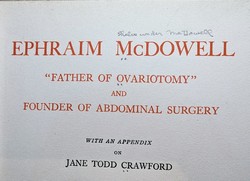

NOTE: This article has been modified from the original Wikipedia article on Marcia Crocker Noyes. The article itself is well-written with interesting images of the subject. I would encourage you to visit it. The second insert is from book ML-0736 in my personal library and shows in pencil, the incredibly small handwriting of Marsha C. Noyes.

Sources:

1. "Marcia, Marcia, Marcia" MedChi Archives blog.

2. "Marcia C. Noyes, Medical Librarian" (PDF). Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 35 (1): 108–109. 1947. PMC 194645

3. Smith, Bernie Todd (1974). "Marcia Crocker Noyes, Medical Librarian: The Shaping of a Career" (PDF). Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 62 (3): 314–324. PMC 198800Freely accessible. PMID 4619344.

4. Edward Caledon BRUCE (1825-1901)"

5. Behind the scenes tour MedChiBuilding