UPDATED: Scientific thought today is a given. Today most of us believe something only after it is proven factually. A scientist is recognized by the capacity to change a position if the appropriate experiments, demonstrations and facts against their position are proven. A scientist holds a healthy position of doubt and even if their positions are proven for a long time, they are willing to accept a scientific counterproposal.

When a belief or a position is supported only by a belief without proof, then it falls into the realm of suppositions and religion. In this article I will not discuss this.

The above is written to support why at the time Andrea Vesalius’ opus magnum “De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem” was condemned by so many, and how Vesalius’ words ushered the beginnings of scientific thought.

Anatomical and medical teachings flourished with the Greeks and attained its peak with Galen of Pergamon (129AD - 200AD), called by many (Vesalius included) “prince of physicians”. Galen was known for his many published works and his writings were translated into Arabic. This was important, because with the invasion of Rome of Greece many of the published works were lost and later the only way to read Galen was to translate his works back into Greek or Latin. Also many books were lost during the Dark Ages.

After the Dark Ages decline of Medicine, the “light” of the Renaissance brought with it the belief that the Ancient Greeks were never wrong and that if anything was wrong, it was the quality of the translation and the interpretation of the works. Early in his career and because of his knowledge of languages, Vesalius was one to work as a translator for commentaries that were made on Galen. Because of his personal dissection skills and his direct observation of the human body Vesalius started to encounter a problem: what was being taught as human anatomy by Galen’s works was wrong. In many cases Vesalius found clear evidence that Galen used goat, dog, and ape anatomy instead of human anatomy to write his works. This was a slow process of breaking with Galenic teachings. Even in the first edition of the Fabrica (1543) Vesalius, even questioning Galen, would not go too far.

In 1540, three years before the publishing of the Fabrica, Vesalius performed a public anatomy in Bologna. There is a well-written and translated diary of the dissection published by Baldasar Heseler, which many say earned him a place in the title page of the Fabrica. Heseler describes Vesalius’ dissection and lectures as well as the fierce discussions between the host, Matthaeus Cortius (1475 – 1542) and Vesalius. The elderly Cortius, Galen’s book in hand, discussed the impossibility of what Vesalius was demonstrating, arguing that Galen “just cannot be wrong”. This discussion was reenacted during one of the lectures by Rebecca Messbarger, Ph.D. at the “Vesalius and the Invention of the Modern Body” interdisciplinary symposium.

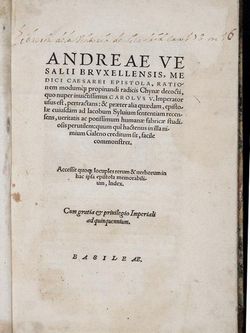

With the publication of the Fabrica the reaction of many Galenists was fierce, probably none more caustic than Jacobus Sylvius (1478 - 1555). Sylvius was a teacher of Vesalius and saw his anti-Galenic position as treason. Known for his propensity to foul language, Sylvius started a personal was against Vesalius, even publishing a small book where he called Vesalius a “madman” plus “purveyor of filth and sewage, pimp, liar, and various epithets unprintable even in our own permissive era” (excerpt from Magner, 1992). Sylvius’ publication was entitled “Vaesani cuiusdam calumniarum in Hippocratis Galenique rem anatomicam depulsio” (A refutation of calumnies by a certain madman against Hippocratic and Galenic anatomy). Garrison (2015) explains the play on words where Sylvius transforms “Vesalii” into “Vaesani” – the madman.

Initially Vesalius tried to be conciliatory and scientific, trying to persuade his opponents with the facts as seen in the human body. His final argument was published in October 1546 in “Epistola rationem modumque propinandi radices Chynae dedocti“ a publication known to many as the “Epistle (letter) on the China Root”. Vesalius used the excuse of writing on a controversial medicinal plant as the venue to explain in detail the reasons why he deemed Galen wrong in many aspects of human anatomy. The “Epistle on the China Root” was printed in Basel by Johannes Oporinus and the introduction was written by Andreas Vesalius’ brother Franciscus. The "Epistle on the China Root" has recently been translated (2015) by Dr. Daniel Garrison, one of the authors of the "New Fabrica".

Personal note: It is clear to me that Vesalius is not the first to promote scientific thought processes, but he is the one that used human anatomy to start the debunking (and acceptance) of portions of what was known at the time in that particular arena. Dr. Miranda

Sources

1. “Jacobus Sylvius (Jacques Dubois) 1478-1555 – Preceptor of Vesalius” JAMA (1966) 195 13; 1147

2. "Andreas Vesalius; The Making, the Madman, and the Myth" Joffe, Stephen N. Persona Publishing 2009

3. “A History of Medicine” Magner, LN Ed. M Deckker Pub 1992

4. “Vesalius: The China Root Epistle. A New Translation and Critical Edition” Garrison DH, 2015 Cambridge University Press

5. “Andreas Vesalius' first public anatomy at Bologna 1540 – An Eyewitness Report by Baldasar Heseler” Eriksson, R 1959 Almquist& Wiksells Boktryck