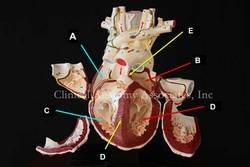

[UPDATED] The term [atrium] is Latin, its plural form is [atria]. The atrium was the center hall of a Roman home, around which the rest of the rooms opened. Since the atrium was the first area of the house that was entered once passing through the front door, the term [atrium] has been used to describe the "entrance hall', such as the atrium of a hotel. The atria are the two superior chambers of the heart. (see image, items "A=right atrium" and "B=left atrium")

[UPDATED] The term [atrium] is Latin, its plural form is [atria]. The atrium was the center hall of a Roman home, around which the rest of the rooms opened. Since the atrium was the first area of the house that was entered once passing through the front door, the term [atrium] has been used to describe the "entrance hall', such as the atrium of a hotel. The atria are the two superior chambers of the heart. (see image, items "A=right atrium" and "B=left atrium")

An interesting question is why are the atria called so, since they are part of the heart, and not just the entrance?. The reason is that early anatomists considered the heart to be composed only by the ventricles. The atria were then chambers where blood would wait before entering the "heart proper", ergo [atria].

Each atrium has a smooth wall (sinus venarum) and a muscular extension akin to a closed-end bag. These are the atrial appendages or auricles. Anatomically they are quite different. The right atrial appendage communication or opening to the right atrium is wide and allows blood to easily flow from and to the atrium. On the contrary, the left atrial appendage has a very small opening (ostium) and its morphology is convoluted with lobulations and a complicated mesh of atrial muscle wall.

The very structure of the left atrial appendage is quite conducive to the formation of clots in atrial fibrillation (AFib). These anchored clots (thrombus/thrombi) can detach and become free clots (embulus/emboli) that will enter the blood stream, pass into the left ventricle, then though the aortic valve, and then pass into the ascending aorta and main circulation. Unfortunately, two of the first arteries that arise from the aorta are the common carotid arteries that take blood to the brain and these thrombi can cause a brain stroke.

Personal note: On November 7, 2023 Dr. Randall K. Wolf invited me to a seminar where we reviewed the anatomy of the left atrial appendage, the problems it can cause in atrial fibrillation as a cause for stroke, and the reasons for its exclusion in AFib surgery.

Image property of:CAA.Inc.. Photographer:D.M. Klein