"No anatomical structure has the moral obligation to be where they are supposed to be"

Not only may an anatomical structure be absent, such as in the case of renal aplasia or agenesis, or in the case of a non-existent circumflex coronary artery, but sometimes extra structures can be found. Such is the case where a kidney can present two or even three ureters, all functional. Double inferior vena cavae, cervical ribs, lumbar ribs, the list goes on and on!

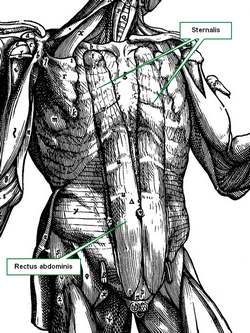

Muscles can be added to this list, again, with absence of a muscle, or with new and completely unexpected attachments. An example of this is the presence of a continuation of the rectus abdominis muscle into the chest region, a variation called a sternalis muscle.

The accompanying image shows the sternalis muscle in one of the "muscle plates" of De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, published in 1543 by Andreas Vesalius. This image was criticized by showing a muscle that does not exist, although Vesalius clearly stated in the text of his book that this was an anatomical variation that he had seen.

For many decades surgeons had to operate and "see what they could find". There were the days of the exploratory laparotomy. After the discovery of the application of X-rays by Wilhem Konrad Roentgen (1845 - 1923) and the incredible advances in imaging techniques including CT-scan, MRI, PET, etc, the surgeon is now not usually surprised by anatomical variations.

There are areas in the body that have an high rate of anatomical variation, such as the hepatobiliary region, which includes the "Triangle of Calot". In this area, the standard anatomy is found only in 64% of the cases! In the rest, expect the unexpected. Lahey (1948) states "...the fact that cholecystectomy is a dangerous operation. It is dangerous unless one realizes.... that anomalous anatomy is very common". Today the dangers are less, because of better visualization and technology, but anatomical variations are still there.

Another area where anatomical variations are extremely important is the heart's coronary circulation. Anatomical variations can cause different cardiac dominance. Normal anatomy states that there are two coronary arteries, yet, up to five separate coronary arteries arising directly from the ascending aorta have been described! There is one variation where the left coronary arises from the right coronary artery, effectively having only one artery arise from the aorta and being in charge of all the arterial supply to the heart. What happens if this single artery stenoses? Bear in mind that this is not an "anomalous" vessel, it is just an anatomical variation.

Sources:

1. Lahey DH, discussing the paper "Partial Hepatectomy with Intrahepatic Cholangiojejunostomy" by Wilson H, and Gillespie CE, Ann Surg. 1949 June; 129(6): 756–765

2. "Renal aplasia is the predominant cause of congenital solitary kidneys" Hiraoka, M et al Kidney Int. 2002 May;61(5):1840-4.

This article is the second in a series of three; Click here for the first article.

TO CONTINUE READING: CLICK HERE